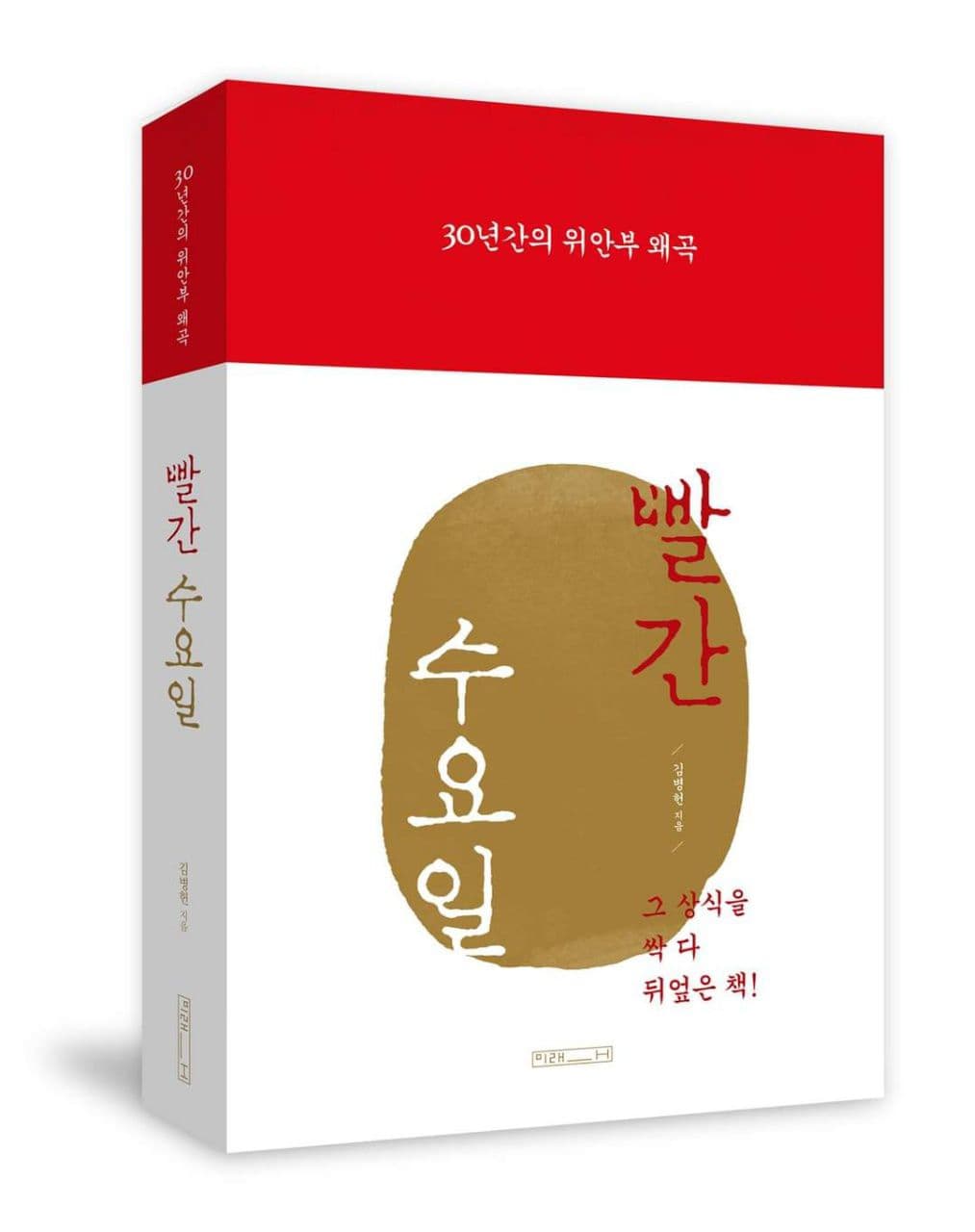

「赤い水曜日 30年間の慰安婦歪曲」

金柄憲 著

発売中!

http://www.yes24.com/Product/Goods/103076869

**********************************

【本の紹介】

国民を騙して世界を騙して

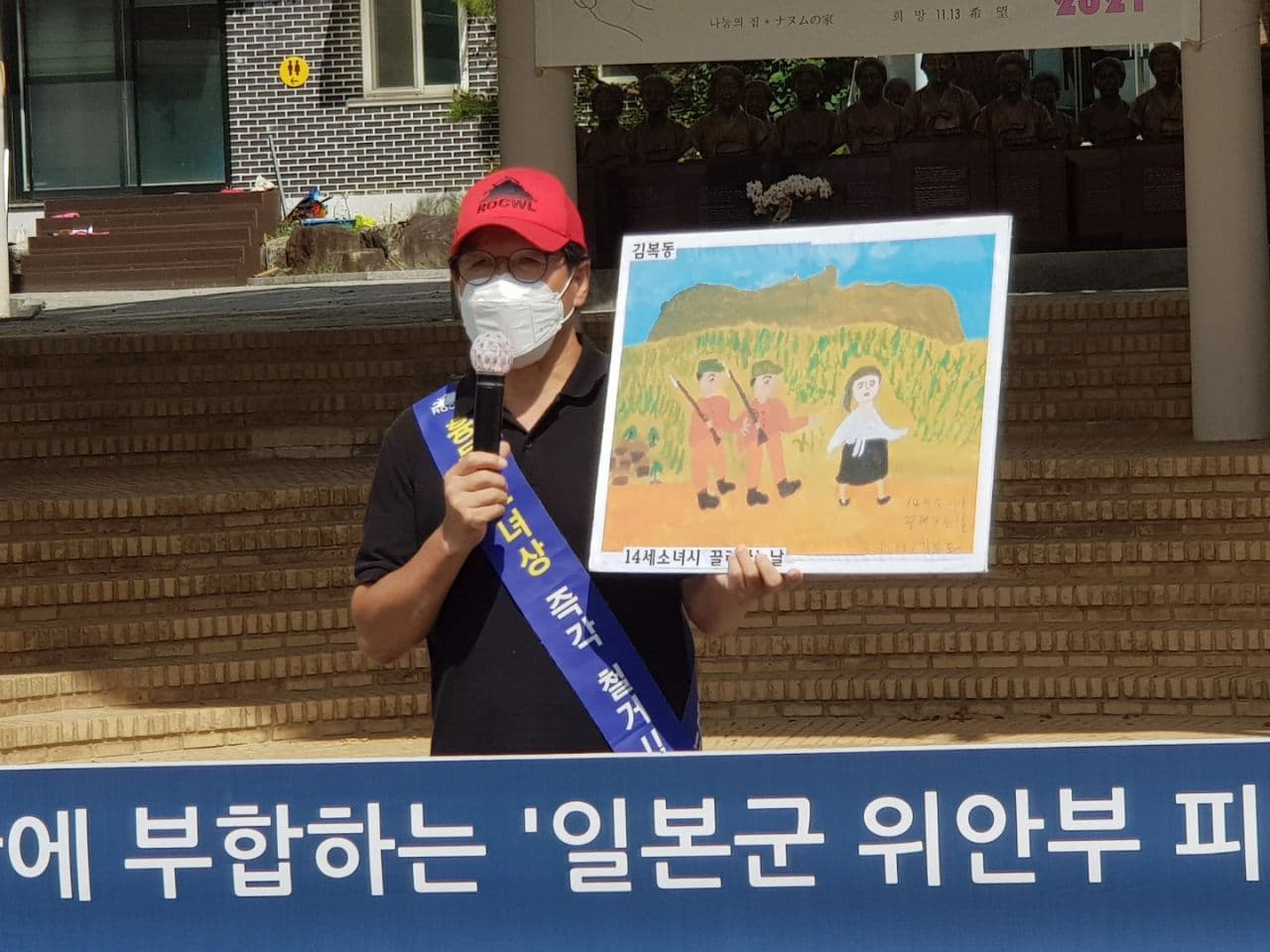

漢文学と史学を専攻した著者の金炳憲(キム·ビョンホン)所長は、教科書執筆者たちに「死神」のような人物として知られている。 教科書に記載された歴史歪曲と誤りを執筆者と争い、多くの修正を引き出したためだ。 著者が慰安婦問題に深く関わってきたことも、小学校『社会』の教科書に載った’水曜集会’写真の中の子供たちを見るようになってからだった。 水曜集会がある度に子供達を集めておいて’性奴隷’、’集団強姦’、’戦争犯罪’など歪曲された慰安婦の認識を植え付け暴力と憎悪心を培養する姿をただ傍観するだけではいられなかったという。 日本軍が朝鮮女性を強制的に連れていったという叙述について執筆者が何の証拠も返事も提示できずに、性に対する否定的認識と暴力性を子供たちに植えつけることが正しいかを悩み、ついにピケットを持って慰安婦少女像のそばに立った。 集まりを作って慰安婦歪曲中断を要求する集会を続けながら、結局、『赤い水曜日』という本を書くに至った。

******************************************************* 【 目次 】

プロローグ

第一部 ’慰安婦’という記憶との闘争

第一章 訴訟の主役、赤いワンピースと革靴の李容洙・15

第二章 記憶との闘い、情報公開を請求する・34

第三章 諦めきれない権利、李容洙と吉元玉を刑事告発する・44

第四章 野心が明らかになった共謀者たち・54

[付録1]さらに深く見る・79

第二部 信じられない司法部の判決文

第五章 1・8でたらめ判決文を解剖する・95

第六章 4・21でたらめ判決文、慰安婦も選び出すのか?・146

第七章 崖っぷちのクマラスワミ国連報告書・168

[付録2]さらに深く見る・188

第三部 国民を騙し、世界を欺く聖域化運動

第八章 40ウォンに売られた金学順を称える日・195

第九章 称える日と「慰安婦被害者法」・214

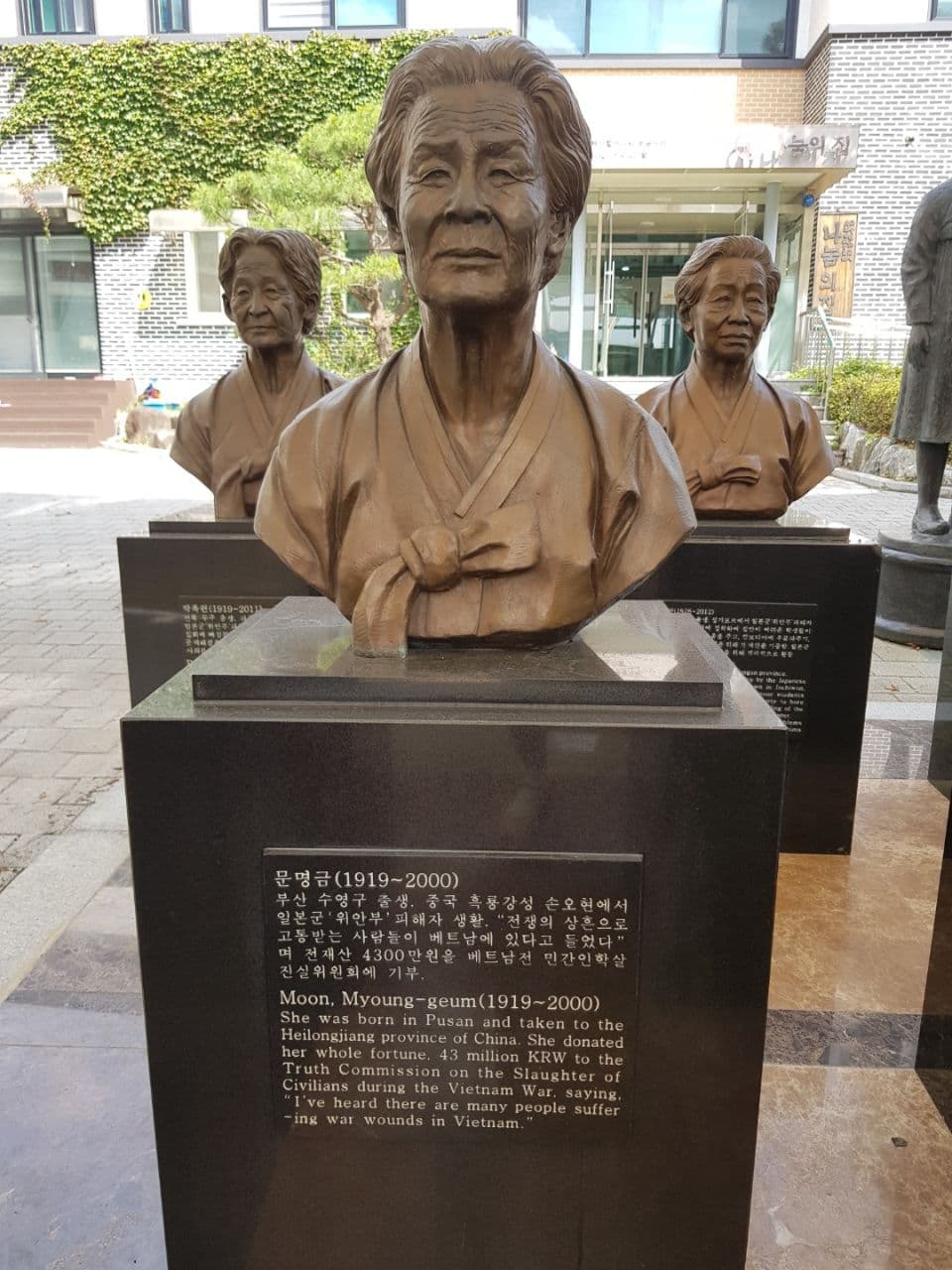

第十章 平和という名前の少女像・241

[付録3]さらに深く見る・256

第四部 30年間の慰安婦の歪曲、赤い水曜日

第十一章 尹美香(ユン・ミヒャン)、そして25年間の水曜日・265

第十二章 道に外れた保坂裕二氏 訴訟を起こす・292

第十三章 教科書に載った慰安婦・321

[付録4]さらに深く見る・346

エピローグ – 1,500回の水曜デモで明らかになった30年慰安婦運動の問題、何事も正直であることが正解・352

・特別付録-そこも愛はあった・357

【 著者について 】

成均館大学校 大学院 漢文学科 学士修士博士課程修了

[元]成均館大学講師 暻園大学講師

『國譯思斎集』 [アダムエンダーリ-共訳]

孝宗大王·英陵の擇山論争

国史教科書研究所所長、慰安婦法廃止国民行動の代表。

空の下、最初の町として知られている慶尚北道英陽郡の小さな田舎町で生まれた。 幼い頃から字を筆で書く書道が好きで始めたのが漢文の勉強だった。 漢文をしてこそ書道がまともにできると思って成均館大学校に入学して漢文学の勉強を始めた。 大学院に進学して勉強がてら儒教経典13経のうち漢字語源を整理した「邇雅注疏」の翻訳作業は彼にとって韓国の歴史立て直し活動の土台を作ることになった。 韓国の歴史用語を分かりやすく記述するために教科書を見て、歴史歪曲の深刻さを確認したのだ。 遅ればせながら史学科博士課程を修了したのもその影響が大きい。

2014年から「国史編纂委員会」、「韓国学中央研究院」、「韓国教育課程評価院」、「EBS韓国史講義」などで問題を提起し、絶えず現場と闘いながら教科書の誤りを正してきた。

彼が慰安婦問題に飛び込んだのは小学校『社会』の教科書に載った水曜集会の写真の中の子供たちを見てからだった。 水曜集会がある度に子供達を集めて’性奴隷’、’集団強姦’、’戦争犯罪’など歪曲された慰安婦認識を注入させる姿だ。 しかも、教科書執筆者が日本軍が朝鮮人女性を強制的に連れて行ったということに対し何の証拠も返事も提示できないという呆れた現実に直面し、そのまま傍観することはできなかった。 慰安婦問題は成人の領域の問題であり、性的アイデンティティが確立されていない子供たちに歪曲された性に対する意識と憎悪心を与えてしまう。 一体この世のどこの国が、そのような暴力的な性質を子どもたちに植えつけようとするだろうか。 これこそが彼がピケットを持って慰安婦少女像の隣に立つしかなかった理由だ。 現在、彼の主張に同意するメンバーが集まり慰安婦歪曲中断を要求する集会を続けている。 この活動が『赤い水曜日』の出発点となった。 この本は、これからこの国の慰安婦の歴史歪曲の解毒剤になることだろう。

******************************************************* VIDEO

*******************************************************

<参考>

文春オンライン 2021.9.22 黒田 勝弘https://bunshun.jp/articles/-/48743