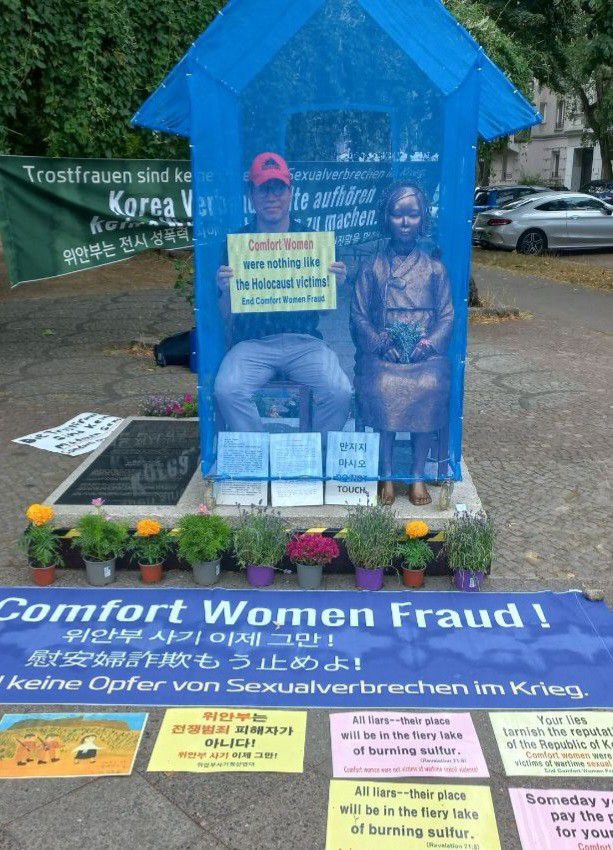

韓国市民団体が結束した「慰安婦詐欺清算連帯」から朱玉順代表、李宇衍博士、 金柄憲所長が2022年6月25日(土)出国、7月1日帰国で独ベルリンを訪問。ドイツ「コリア協議会」の嘘中断と少女像の自主撤去を要求するための活動を行いました。

ベルリン現地では6/26-29連続四日間の慰安婦像での街頭活動、ミッテ区長への意見書、現地韓国人との懇親会を行うなど精力的な活動を行いました。」

「慰安婦詐欺清算連帯」の皆様お疲れさまでした、そして有難うございました!

ドイツを離れる – 2022. 6. 30.

ブランデンブルク空港から – 2022. 6. 30.

【帰国報告】無事到着しました。 – 2022. 7. 1. 仁川空港

************************************************************

「慰安婦詐欺清算連帯」訪独ベルリン 纏め

第一日目(2022.6.26) http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17080

第二日目(2022.6.27) http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17077

第三日目(2022.6.28) http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17137

第四日目・活動最終日(2022.6.29)http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17145

まとめ(2022.6.25-7.1) http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17159

ミッテ区長への意見書

日本語

http://nadesiko-action.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Statement-to-Mayor-of-Mitte-District_JPN.pdf

英語

http://nadesiko-action.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Statement-to-Mayor-of-Mitte-District.pdf

**************************************************

< 海外 報道 >

ドイツ TAZ 6/26/2022

„Trostfrauen“-Mahnmal in Berlin

:Streit an der Friedensstatue

Koreanische Geschichtsrevisionisten leugnen sexualisierte Verbrechen im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Berlins Korea Verband hält mit einer Aktionswoche dagegen.

ベルリンの「慰安婦」碑:平和像での対立

韓国の歴史修正主義者がWW2の性犯罪を否定。ベルリンのコリア協議会が今週対抗措置

https://taz.de/Trostfrauen-Mahnmal-in-Berlin/!5860795/

This Week in Asia 25 Jun, 2022 Julian Ryall

Why is a South Korean fringe group backing Japan’s position on WWII ‘comfort women’?

https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/article/3182991/why-south-korean-fringe-group-backing-japans-position-wwii-comfort-women

< 日本 報道 >

現代ビジネス2022.07.22

韓国で「親日派」と罵倒されても…私がすべての「慰安婦像」を撤去したいワケ

ドイツでデモ「朱玉順氏」が語ったこと

https://gendai.ismedia.jp/articles/-/97435

JAPANFoward July 20, 2022

Statues of Division: Korean Intellectuals Contest ‘Comfort Women’ Monuments By Kenji Yoshida

https://japan-forward.com/statues-of-division-korean-intellectuals-contest-comfort-women-monuments/

産経 2022/6/29

独の慰安婦像撤去求める韓国団体が苦戦 街頭活動妨害、面会キャンセル

https://www.sankei.com/article/20220629-SDEX3UYBWZM5TINK4ZX2IPFF5E/

JAPAN Foward June 20, 2022

South Korean Group Tackles the Antagonism and Hatred Spread By Comfort Women Statues

https://japan-forward.com/south-korean-group-tackles-the-antagonism-and-hatred-spread-by-comfort-women-statues/

JAPAN Foward June 13, 2022

South Korean Civic Group to Berlin: Remove the Comfort Women Statue

https://japan-forward.com/south-korean-civic-group-to-berlin-remove-the-comfort-women-statue/

< 韓国 報道 >

聯合ニュース 2022-06-30

[특파원 시선] 소녀상 앞 철거촉구 극우시위 막으려면

https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20220630180400082

CBSノーカットニュース 2022-06-29

친일 극우 중심 ‘위안부 합의 복원’…”즉각 중단하라”

https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5779096

中央日報 6/29(水)

保坂祐二教授「ドイツで少女像撤去デモ、歴史不正勢力の行動禁止法案を制定しなければ」

https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/6c423e6deb3cb3e3b684fa9d59899ef7cdd53e9e

국민일보 2022-06-28

국힘 이태규 “베를린 ‘소녀상 철거 시위’ 단체, 보수 자격 없어”

https://news.kmib.co.kr/article/view.asp?arcid=0017222890&code=61111111

JTBC 2022-06-27

독일까지 날아간 극우단체, 소녀상 철거 주장 ‘황당 시위’

https://news.jtbc.joins.com/html/020/NB12064020.html

中央日報 2022.06.27

ドイツ・ベルリンに行った韓国市民団体、少女像撤去主張…「詐欺はやめよ」

https://japanese.joins.com/JArticle/292558

中央日報 2022.06.28

「韓国人の少女像撤去主張、ドイツ人もあきれている」

https://japanese.joins.com/JArticle/292613

中央日報 2022.06.28

韓国与党議員「ベルリン少女像撤去デモにあ然…韓国国民か日本の極右か」

https://japanese.joins.com/JArticle/292611

Jayupress2022.06.28

베를린 “소녀상 철거” 대항집회에 북한 인공기 티셔츠 할아버지 등장

ベルリン「少女像撤去」対抗集会に北朝鮮Tシャツおじいちゃん登場

https://www.jayupress.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=6709

news.naver 2022.06.26.

한국 극우, 베를린서 “소녀상 철거”…독 시민단체 “이해 불가” 맞불 집회

韓国極右、ベルリン「少女像の撤去」

独市民団体「理解不可」対決集会

https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/international/europe/1048544.html

https://n.news.naver.com/article/028/0002596231

https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/ff3ddad02363b27b5c841793941f787491cf16a3

Hankyoreh Jun.27,2022

Far-right S. Korean protest of Berlin comfort women statue met with counter-rally

https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/1048670.html

************************************************************

【慰安婦詐欺清算連帯 への支援】

Paypal cleanmt2000@gmail.com 金柄憲所長、国民行動への支援

チャンネルfujichan (国民行動に送金します)

後援口座 ゆうちょ銀行

店名 五五八

店番 558

口座番号 2629662

ミヤモトフジコ

【チャンネルfujichanへの後援口座】 (個人)翻訳頑張ります。

店番098

山口銀行 5096982

ミヤモトフジコ

댓글 12개