CONTRACTING FOR SEX IN THE PACIFIC WAR:

A RESPONSE TO MY CRITICS

J. Mark Ramseyer

01/2022

PDF版ダウンロード ※新しいタブに表示されます

http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/papers/pdf/Ramseyer_1075.pdf

【 Abstract 】

In “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War,” International Review of Law & Economics (IRLE) (2020), I explored the economic logic behind the contracts made by Japanese and Korean prostitutes with the brothels at which they worked. Among the terms of the contracts that I tried to explain were the way in which they coupled a large initial payment with a maximum period of service. I sought to interpret these and other contractual terms as addressing classic economic dilemmas.

My article provoked massive criticism. However, virtually none of the critics attacked my economic analysis of the contracts. Indeed, most of my critics did not even mention my analysis of the contractual terms — even though that was the focus of my article and was the basis for its publication in the IRLE.

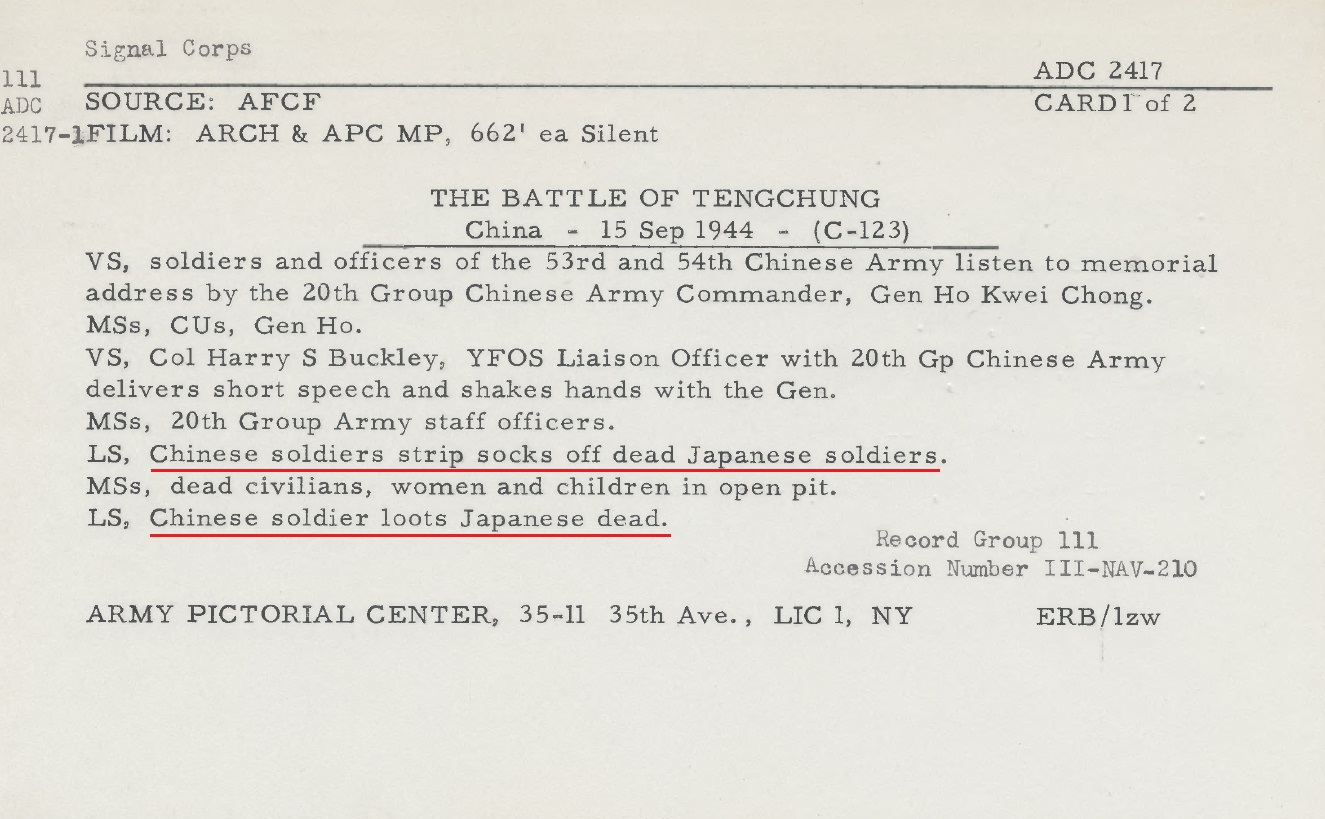

Instead, some critics complained that I did not examine actual prostitution contracts. Readers of my actual article will know that I never claimed to have a data set of actual contracts. To the best of my knowledge, very few actual contracts survived the war. What I did rely upon—as I make clear in my article—is information about the prostitution contracts from government documents, wartime memoirs, newspaper advertisements, a summary of a comfort station accountant’s diary, and so forth.

Other critics compiled a long list of asserted mistakes concerning the accuracy, relevance, and interpretation of citations in my article. I respond to these claims below. Most of them are not mistakes at all. A small number of them are mistakes, but they do not affect my analysis of the contract terms.

Most critics emphasized the immorality of the comfort women system. In particular, some critics claim that I ignored the fact that some women were deceived into becoming comfort women and were cheated and otherwise mistreated by owners of the comfort station brothels. Readers of my actual article will recall that I mention these points in my article.

Most of the critics insist that large numbers of Korean women were forcibly conscripted (at gunpoint or hauled away against their will) by the Japanese army in Korea. My IRLE article does not address this issue, but I discuss it in this response. The claim is false: Korean women were not programmatically and forcibly conscripted by Japanese soldiers in Korea into comfort station work. There is no contemporaneous documentary evidence of forcible conscription. Neither is there any evidence for over 35 years after the war ended in 1945. Only in the late 1980s did some Korean women begin to claim that they had been forcibly conscripted.

Crucially, in 1983 a Japanese writer named Seiji Yoshida wrote a best-selling book claiming that he and a posse of soldiers had dragooned Korean women at bayonet point and raped them, before sending them off to serve as sexual slaves. A famous 1996 UN report on the conscription of Korean women relied on this book, and it is in the wake of the book that a small number of Korean women began claiming that they had been conscripted even though some of them had earlier given different accounts. Before he died, Yoshida admitted that he had fabricated the entire book. Yoshida’s fabrication attracted substantial attention in Asia and abroad, including in the New York Times.

The comfort women dispute began with Yoshida’s fraud. Yet this astonishing and crucial fabrication is not mentioned by any of my critics even though many of them are Japan or Korea experts and are surely aware of it.

【 Table of Contents 】

On Studying Wartime Prostitution (including a response to Gordon-Eckert and Suk-Gersen)

Appendix I: A Response to Stanley, et al.

Appendix II: A Response to Yoshimi

Appendix III: Information about Comfort Women Contracts

Bibliography

*************************************************

<参考>

ハーバード大ラムザイヤー教授 論文 1991年「芸娼妓契約-性産業における信じられるコミットメント」、2021年「太平洋戦争における性サービスの契約」

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15670

萩生田文科大臣、ラムザイヤー教授論文について国会で答弁「自発的かつ自由な研究活動を尊重すべき」

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15772

4.24【緊急シンポジウム】ラムザイヤー論文をめぐる国際歴史論争 (永田町/星稜会館)

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15792

ラムザイヤー教授からのメッセージ(日本語文字起こしと韓国語訳)

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15867