米国下院 慰安婦決議 撤廃

オバマ大統領府への請願

下院121号決議を撤廃し

韓国のプロパガンダと嘘による国際的嫌がらせの助長をやめることを

請願します

韓国は、「ディスカウント・ジャパン(日本を貶める)」というキャンペーンのもと、ホロコーストのイメージを使い、吉田清治が後に嘘であったと自白した「慰安婦」という捏造を利用しています。口頭での証言は強制・拉致の証拠にはなり得ません。2007年可決米国下院121号決議は、捏造に基づくものです。これは、韓国に大東亜戦争での日本の行いを糾弾する道を与えるものであり、ひいてはメタンハイドレートが豊富に埋蔵されている竹島での、殺人行為、拉致と占領を正当化することにもなります。日米同盟が真にアメリカのアジア太平洋地域の安全保障の礎石であり、地域の安定と繁栄を支えるものであるならば、韓国人による関係悪化を許してはいけません!米国政府は真実と正義に基づいて行動すべきです。

<参考>米国下院慰安婦決議121号 [原文(英語)] [日本語]

署名はこちらから

http://wh.gov/lBwa

★署名方法はこのページの下の方にあります★

署名ご協力のお願い

2007年7月30日(第一次安倍内閣当時)、米国下院を通過した121号決議、いわゆる慰安婦決議。

その内容は『日本政府による強制的な軍隊売春制度「慰安婦」は、「集団強姦」や「強制流産」「恥辱」「身体切断」「死亡」「自殺を招いた性的暴行」など、残虐性と規模において前例のない20世紀最大規模の人身売買のひとつであり、日本は公式に認めて謝罪し、歴史的な責任を負い、現世代と未来世代を対象に残酷な犯罪について教育をしなければならない』というものです。しかもこの決議、下院議員435名中、出席議員はたったの10名。票を取らずにvoice vote”賛成!”の声だけで可決されたものです。

この決議以来、海外における反日・侮日の慰安婦キャンペーンが始まりました。現在では、「日本軍が20万の婦女子を拉致し強制的に性奴隷にした」という捏造が既定事実として、世界に広まっています。

米国内では2013年に入ってから州・郡で慰安婦決議・宣言が採択。その内容は、「20万人、強制、拉致、性奴隷」に加えて、「慰安婦の殆どが韓国・中国人」、「慰安婦4分の3は残虐な仕打ちで死亡」「生き残った慰安婦は性暴力や病気で不妊症になった」「(州の)学校教育に取り入れる」等、ますます酷くなっています。

これら地方議会の決議は、全て2007年下院決議121号が基になっています。

なでしこアクションではホワイトハウスに慰安婦決議撤廃の請願を出し、2013年6月現在、約3万署名集まっています。

この請願は、多く人が注目するホワイトハウスのサイト上で、私たちの慰安婦決議NO!の意思を署名数という形で表すことができます。3万台にとどまらず、5万、10万と署名が増えることを願っています。

署名はオバマ政権から回答が得られるまでの間、継続することができます。回答が何時出るかは分かりません。

私たちの先人の名誉の為に、次世代に誇りある日本を繋ぐ為に、そして、日米韓の真の友好の為にも、一づでも多くの署名をいただけますよう、ご協力心よりお願い申し上げます。

★署名の方法はこのページの下の方にあります★

ジャーナリスト 山際 澄夫 様 からのメッセージ

2012年、米国で「慰安婦」問題を取材しました。

全米で「慰安婦」碑建設を進める韓国系米国人の団体、「慰安婦追悼通り」の創設を提唱するニューヨーク市議ら私が会った関係者すべてが「慰安婦」が「日本軍の強制連行による性奴隷」である根拠と主張していたのがこのマイクホンダ決議(米下院121号決議)であり、河野洋平談話の存在です。この決議と河野談話の撤回がなければ「性奴隷」は虚構だといくら主張しても相手にされないと痛感した次第です。

本来なら河野談話の撤回が先行すべきものでしょうが、請願署名に踏み出した以上、これまでのホワイトハウス請願以上の圧倒的な数をもって請願受理を達成するよう努力していただきたいと思います。

ホワイトハウス請願署名方法

<初めての方> ローマ字(半角英数字)で登録してください。

山田花子⇒Hanako Yamada

①ホワイトハウスの署名サイトへ⇒ http://wh.gov/lBwa

(最後の4文字は 小文字エル B w a)

※アカウント作成は13歳以上、1メールアドレスにつき1アカウント

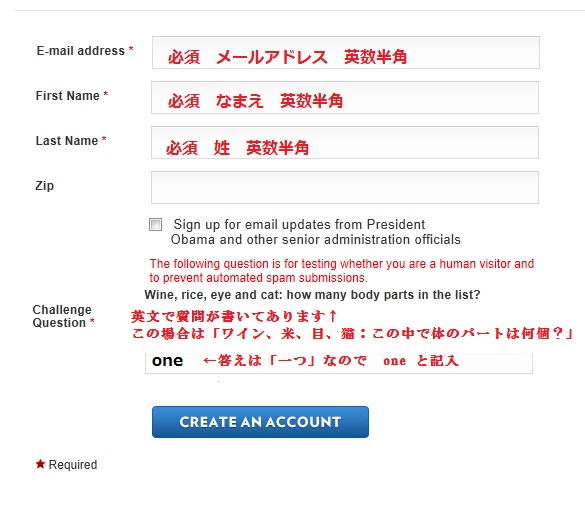

②下へスクロールして、[CREATE AN ACCOUNT]青いボタンをクリック。

③半角英文字で、メールアドレス、名前、姓を記入します。(zip は記入必要なし)

署名後に署名した人の氏名が表示されますが、「T. S.」のように姓はイニシャルだけになります。メアドは公開されません。

④Challenge Question の質問の答えを英単語・数字で記入します。

質問と答えが分からない場合は、こちらの質問・回答リストを参考にしてみてください。

⑤入力したら[CREATE AN ACCOUNT]青いボタンをクリック。画面が変わります。

⑥5分くらいすると、Whitehouse.gov (info@messages.whitehouse.gov) から、登録したアドレスにメールが送られてきます。メールを開きます。

★この段階で、ホワイトハウスからメールが来ない方へ:メールアドレスによってはサーバー側がホワイトハウスからのメールを受信しないことがあります。Gmail, Yahoo 等のフリーのメールアドレスは大丈夫です。お試しください。Gmail 作成はこちら

⑦メールの内容

(日本語訳=ホワイトハウスのアカウントを作るまでもう少し。有効なアドレスであることを認証するために下のリンクをクリック又はブラウザにコピー・貼り付けしてください)

https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/user/reset/…. (数字やアルファベット) …..

(以下省略)

↑

ホワイトハウスから送られてくるメールにこういう長いURLがあるので、これをクリックします。

クリックしても移動しない場合は、URLをコピーしてブラウザ(Internet Explorer等)のURL欄に貼り付け、Enterキーを押します。

これでログインとなりました。

⑧自動的に先ほどの請願署名のページが開くはずですが、先ほどの請願署名ページが開かない場合は再度 http://wh.gov/lBwa を開いてください。

ログイン状態になったので[✓SIGN THIS PETITION]緑のボタンがあるはずです。ここをクリックすると署名完了です。

自分の名前がページに表示されます(署名後はリストの2番目に名前が、少し濃いグレーの枠の中に表示されます)

⑨アカウント情報

登録の際に送られてきたメールにある

e-mail: XXX@XXX.com

password:xxxxxxx

の登録情報は、再度ログインするために必要です。必ず控えておいてください。

<既に登録済の方 署名方法>

①ホワイトハウスの署名サイトへ⇒ http://wh.gov/lBwa

②下へスクロールして、[SING IN]青いボタンをクリック。

③前回登録した E-mail とホワイトハウスからのメールに書いてあった PASSWORD を入力

[LOG IN]青ボタンをクリック

④開いたページの[✓SIGN THIS PETITION]緑のボタンをクリックして署名完了です。

<一つのメールアドレスで一つのアカウント登録>

★パソコン1台で1アカウント登録ではなく、1メールアドレスで1アカウント登録です。一台のパソコンをご家族など数名で共有している方は、それぞれのメールアドレスでご家族分のアカウント登録と署名ができます。

★メールアドレスはGmail等で無料で作成できます。Gmail 作成はこちら

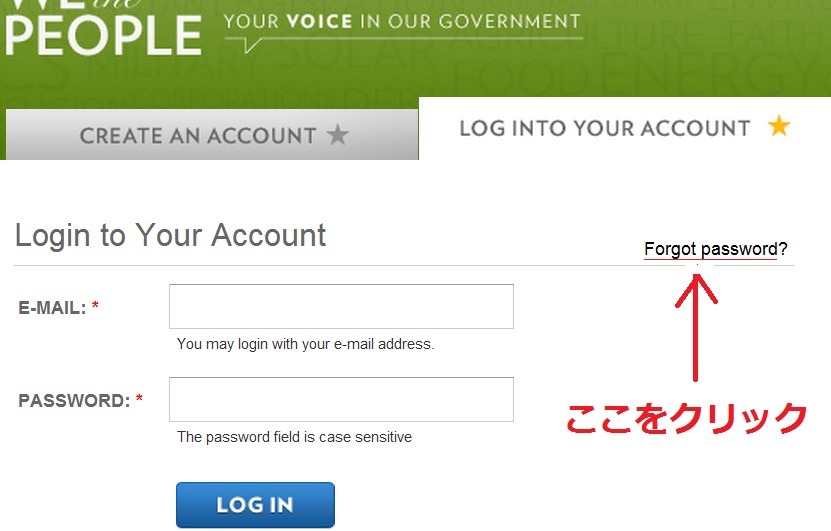

<パスワードを忘れた 又は 登録したはずなのにログインできない方>

①ホワイトハウスの署名サイトへ⇒ http://wh.gov/lBwa

(最後の4文字は 小文字エル B w a)

②下へスクロールして、[SIGN IN]青いボタンをクリック。

③Forgot password? をクリック

④E-mail欄に登録したメールアドレスを間違えないように 半角英数字でコピペ又は記入。

[SUBMIT]青ボタンをクリック

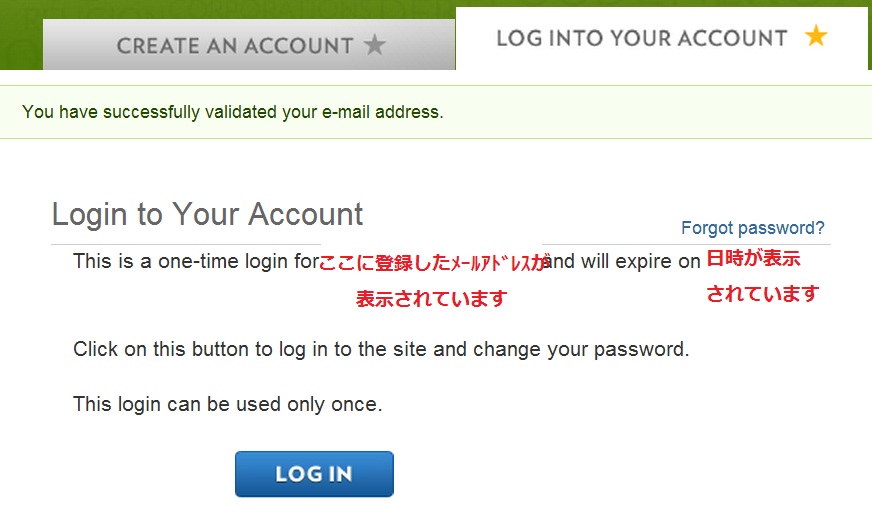

⑤ホワイトハウスからメールが届く

件名:Replacement login information for メールアドレス at We the People: Your Voice in Our Government

本文:A request to reset the password for your account has been made at We the

People: Your Voice in Our Government.

You may now log in by clicking this link or copying and pasting it to your

browser:

https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/user/reset/….数字・番号…..

↑

このURLをクリックまたはコピーしてブラウザのURL欄に貼ってEnter

⑥[LOG IN] 青ボタンをクリックしたらログイン状態になります。

⑦パスワード変更の必要が無ければ http://wh.gov/lBwa へ移動。

開いたページの[✓SIGN THIS PETITION]緑のボタンをクリックして署名完了です。

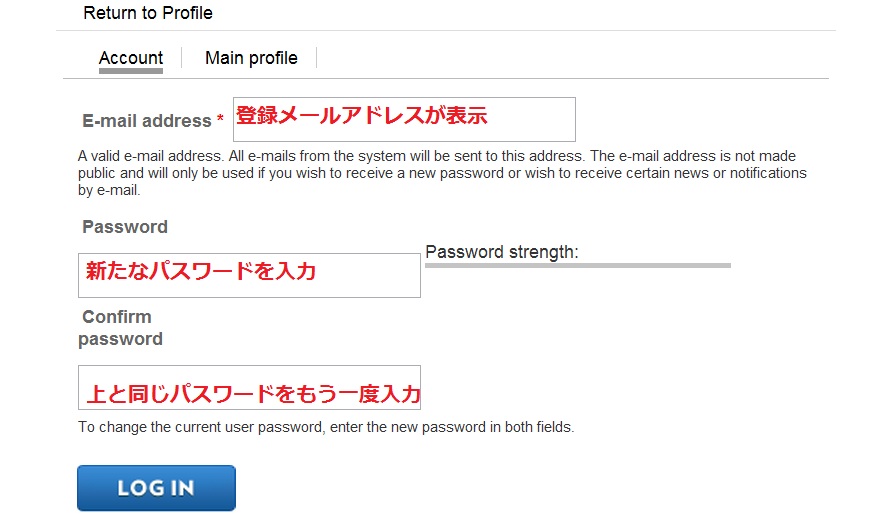

⑧パスワード変更したければ、新たなパスワードを2回入力して[LOG IN]青ボタンをクリック

⑨これでパスワード変更となりました。

次に http://wh.gov/lBwa へ移動。

開いたページの[✓SIGN THIS PETITION]緑のボタンをクリックして署名完了です。

こちらのブログにパスワード再発行の方法(登録方法も)が分かり易く説明されています。

ひめのブログ 「ホワイトハウスへ直請願!!1か月で25000署名集めるよ2!!」

※別の請願の署名方法の解説ですが手順は同じです。

パスワード再発行が上手くいかない場合は、別メールアドレス(Gmail等のフリーのメアドを利用可)で新たに登録する方法もあります。

<登録情報変更の方法>

名前を漢字で登録した方は念のためローマ字(半角英数字)に直してください。

①一度ログインの上こちらのURLへ https://petitions.whitehouse.gov/user/

②画面中央下の [Edit Profile/Change Password]青ボタンをクリック

③Account タブ をクリックすると パスワード変更の画面。 Main Profileタブ をクリックすると名前、都市、国等の登録情報画面になります。

④登録情報変更の上 [LOG IN]青ボタンをクリック

これで変更完成です。変更パスワードは大文字小文字の混ざったPassword strengthの高いものが良いようです。

<説明動画>

※別の請願の署名方法ですが、手順は同じです

ホワイトハウスへの署名方法

【魔都見聞録】慰安婦碑撤去署名にご協力を[桜H24/5/28]

慰安婦碑撤去に関するオバマ大統領宛の請願書(署名方法)

慰安婦碑撤去に関する請願書(署名)・パスワード変更方法

参考資料

産経デイリー古森さんのPBSでのインタビュー(2007年3月 米TV番組から)

東海の2千メートル海底から採取した「燃える氷」 2012年05月30日09時03分 [ⓒ 中央日報/中央日報日本語版]

韓国人売春婦が韓国政府とアメリカを訴えた記事(ニューヨークタイムズ紙) (英文)

米軍による朝鮮戦争中の慰安婦の現状報告 (英文)

朝鮮の新聞記事のデータから真実を見る。日本軍が20万名もの少女を誘拐したなどという記事は皆無である!

宣伝チラシ

有志の方が作成して下さった「なでしこアクション請願署名PRチラシ」(PDF)です。ご利用ください。

併合当時に朝鮮半島の議員やってたほとんどは

朝鮮人だったし、警察官も朝鮮人が職務についていた

事もきちんと提示したほうが良いと考えます。

もう既に書いて居る人もいますがテキサス親父の調べてくれた1,944年の米軍の調査書に関する動画を各州に拡散すべきだと思います。いまも更なる慰安婦像建立の議会が開かれていると2ちゃんねるで知りました。やっと外務省が抗議をした、との事ですが内容はとても抗議などと言えるものではなく、ただ日本の立場を述べただけである。

本来ならば建立した各市に対して裁判を起こしてもいいくらいである。何もしない日本政府の態度は事実上容認と受け取られてしまいます。

既に米国裁判所は捏造である、と判断したこの件でこれ以上、対日感情を煽られるのは安全保障上でも問題である。

署名いたしました。

最近になって、数々の忌々しい反日活動に対して抗議をされている方々がいることを知りました。自分はまだ独身ですが、兄弟や親戚の子供たちの事を考えると、無知は罪であることを強く思うようになりました。

今後のご活動も微力ながら応援しております。

私も参加したかったんですけど、メールが送られてきませんんでした。英語が全然できない無学なので、よく分からず・・・。署名された方々、ありがとうございました。ほかの方にもこの署名のことを教えます。

ネット上で慰安婦騒動に対する記述をいろいろ検索してきたのですが、誰が書いたかわからない下記の文章は非常に明快達観していて奥が深いです。もし教科書に書くなら、(本来書く必要はないが)このような記載にすべきと思いました。英訳してもよい文章です。

====

古来戦場では、罪のない女・子供が血気に逸った一部の兵士に襲撃・殺害されてきたが、各国の軍隊ではこれを防ぐために、公娼や募集によって軍隊が駐屯する所に、慰安所を設け、強姦や虐殺の被害が最小限になるように心を配った。第二次世界大戦中には、わが国も同様の慰安所を設けたし、ベトナム戦争中には韓国も同様の施設を設けたことが明らかになっている。日本軍は、「悪質な業者によってだまされてつれてこられた女性もいたことを懸念し、文書でそのような行為を行わないように指導しほか、慰安所の衛生にも気を配った。

オランダ人女性が、不当に働かされたスマラン事件の例などもあるが、そういう場合は日本軍は慰安所を直ちに閉鎖し、不当行為の蔓延をふせぐのに努力した。

しかしながら、女性への暴力を防ぐためにこれらの努力が重ねられながらも、一般兵士による女性への暴行が行われたことは確認されている。日本政府は、そういった不幸な経験をした女性に対して、人道的配慮から、「アジア女性基金」を二国間条約とは別に設けている。

http://cooljapon.seesaa.net/article/367584369.html こういったわかりやすい動画を提示するのも策だと思います。アメリカ人はこういってはあれですが馬鹿が多い。そもそも興味がないから適当な知識で議決をするわけです。韓国は金での買収や地方の組織票を武器に像の設置を進めています。興味がないから勉強もしない、ただ有利に動いてくれる在米韓国人の支持が欲しいだけです。だがこの動画やテキサス親父の動画は頭が弱いアメリカ人にも理解できると思います。

コピペで抗議文を送っても全員が同じ文面だ、と逆に日本人による工作だと思われてしまいます。なので言葉よりもこういった写真を提示した動画の方が難波いも効果あると思います。

このWebサイトの英語版は作らないのですか?

歴史認識を訴える韓国の歴史教科書をアメリカで見せるのはどうでしょう?

そして彼らがどれだけ湾曲した自作の歴史を世界中に広めようとしてるか認識させるべき。

Dear Mayor Elizabeth Swift,

I am writing this letter on behalf of all who are concerned about the spread of the Korean myth of sex slavery by the Japanese military that condemns Japan without evidence. The myth has been expressed in various forms of Korean art works, such as painting, photography, and sculpture, for one purpose: to bring shame on the Japanese race.

I believe that you are receiving a number of identical or near identical emails and letters protesting against the proposal that was submitted to your council for installing a monument of Korean comfort women. I do not intend to repeat the same words you have seen in those emails and letters. Instead, I’d like to share with you the information about the Korean comfort women in hopes that it will help you and your council members come to a fair and wise decision.

The word “comfort women” is a literal English translation of the Japanese word ianfu , which is a euphemism for “wartime prostitutes” or “professional camp followers.” It is known that the Japanese military utilized the sexual services of ianfu and that at least a half of those women were Japanese while the rest were Taiwanese and Koreans, who were Japanese citizens until 1945. It is also known that, since the beginning of the organized armies, armies have had professional camp followers and used their services to release the soldiers’ sexual tensions and prevent the soldiers from raping local women. Both the U.S. and Korean military too had comfort stations during the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Thus, the point of discussion regarding the issue of Korean comfort woman is not Japanese military’s having utilized their sexual services but whether or not the Japanese government and/or military was involved in sex trafficking and/or forced mobilization of Korean women for sex.

According to Prof. Byeong-jik Ahn of Seoul National University who led the research on the Korean comfort women and supervised the (1993) publication of surviving comfort women’s testimonies, there is no objective evidence that proves that the Japanese government/military was forcibly mobilizing comfort women. Many researchers concur with the professor. The Japanese military allowed brothel owners–Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese–to follow the Japanese military and provide sexual services; the brothel owners followed the military to make profit; and many impoverished families sold their daughters to prostitution houses to survive. There was no need for the Japanese military to hunt for young women because there were already business establishments that legally provided sexual services. The circumstances which women from poor families faced 70 years ago might be viewed as human right violation in today’s standards, but we should be reminded that prostitution used to be a legal occupation in many parts of the world, that it remained legal in South Korea until 2004, and that even the Civil Rights Act in the U.S. was signed only about 50 years ago. We have come a long way in terms of human right issues in the past 70 years, and therefore, the issue of the Korean comfort women should be understood in its historical context.

The comfort woman first became a controversial issue in Korea in 1989, when author Seiji Yoshida’s (1983) fictional narrative Watashi no Senso Hanzai “My War Crime” was translated into Korean; and since then, extensive research has done to shed light on a number of facts relating to the Korean comfort women. The following eight questions remain unanswered by the Korean activists who have been promulgating the myth of sex slaves by the horrendous Japanese military:

(1) Many years after the publication of Testimonies I, Prof. Byeong-jik Ahn appeared on Korea’s national TV MBC in December of 2006 and stated that there was no objective evidence for forced mobilization of comfort women by the Japanese government/military. Koreans are still making the comfort women an issue in the U.S. and spreading the narrative based on a fictional story. The issue, contentious as it is, is an issue between Korea and Japan. Why are the Korean activists trying to erect monuments and statues in many U.S. cities?

(2) Why has not even one Korean person come out and claimed witnessing a girl being abducted, mobilized, or recruited by the Japanese military? The surviving comfort women’s testimonies are groundless accusations unless there is collaborating evidence, such as a police report by the relatives, to support them, but no such report was ever submitted.

(3) Why did the surviving comfort women’s testimonial narratives change over time? As Chunghee Sarah Soh, a San Francisco State University professor, states in her (2009) book entitled The Comfort Women, “their original published testimonial narratives told very different stories from the current, paradigmatically established image of all former comfort women having been drafted by the Japanese military”(p,101) and “the survivors presented dramatically untruthful versions of their recruitment when they were placed under a spotlight of the political stages of the United States and Japan” (p. 102). Surviving comfort women’s testimonial falsification is also pointed out by Prof. Byeong-jik Ahn.

(4) There were ethnic Korean Congressmen in Japan’s central government and ethnic Korean generals in the Japanese military when Japan and Korea were a unified country (1910-1945). Park Chun-gum (朴春琴/박춘금) was a twice elected Congressman residing in Tokyo. Shigenori Togo (東郷茂徳) was born Park Moo-duk (朴茂徳 / 박무덕), adopted a Japanese name at 5, and served the government as Foreign Minister of Japan (1941-1945). Lieutenant General Hong Sa-ik (洪思翊/홍사익) commanded many Japanese officers and soldiers under him, and he was prosecuted as a B-Class war criminal by the Allies in 1946. Both the government and the military had ethnic Korean personnel. How could the Japanese government/military use a cruel method of recruitment of comfort women only in the Korean peninsula?

(5) Why didn’t politicians, policemen, families and friends in Korea try to stop the alleged rampant abductions by the Japanese military? The population in the Korean peninsula was about 25 million in 1944; and the myth goes 200,000 were abducted as comfort women. Since roughly 12.5 million accounted for the Korean female population, Korean women were abducted roughly at the rate of one in every 60, according to the myth. About 80% of the councilmen in Korea, elected through elections, as well as 80% of the policemen in Korea were ethnic Koreans; but for some reason, they did nothing to stop their fellow Korean women from being abducted, and not a single riot occurred at the time of those abductions.

(6) Why did as many as 802,147 ethnic Korean men submit applications to enlist in the Japanese military during the six-year period from 1938 to 1943? Only 17,364 were accepted and got enlisted: a fierce competition. If the Japanese military was indeed mobilizing their 200,000 sisters and making them sex slaves, what motivated the Korean men to apply to the organization that violated their sisters?

(7) Doesn’t the number 200,000 come from a terminological confusion between comfort women and jeongshindae which is the Korean pronunciation of the Japanese word teishintai that referred to “wartime mobilization of female students for labor services”? The National Service Draft Ordinance was promulgated in 1939 as part of Japan’s war efforts, and the law empowered the Japanese government to draft civilian workers to ensure an adequate supply of labor in strategic war industries. Healthy young females between the ages of 14 and 25 joined “volunteer labor corps” or teishintai to work in factories while healthy young males were drafted as soldiers. Appropriate salaries were paid for their dutiful labor services. If jeongshindae was just another name for comfort women in Korea, what were the Korean female students mobilized for labor services called?

(8) Why do the Korean activists try to ignore the treaty signed by Korea and Japan? The Basic Relations Treaty of 1965 finalized any claim, whether it be from the Korean government or from individual Korean citizens, arising out of Japan’s being in Korea for 35 years. The settlement agreement stipulated that Japan give up the right to all the properties and infrastructure built in the Korean peninsula and give 800 million dollars in grants and soft interest loans to the Korean government. Japan did. The Korean government’s receipt of 800 million dollars was kept secret for forty years in Korea until 2005, but the fact has been known there for the last 8 years. Multiple apologies were made by various Japanese government officials after the signing of the Treaty, and Koreans still demand apologies from Japan.

These questions have not been and will never be answered adequately by the Korean activists who try to propagate the myth of sex slaves by the horrendous Japanese military, for the myth is filled with inconsistencies, contradictions and ambiguity galore.

The proponents of the theory of sex slavery by the Japanese military often claim that the Kono Statement is the evidence for the Japanese military’s forcible mobilization of Korean women for sexual services, but the Statement never acknowledges that the Japanese military systematically coerced women into prostitution. The Statement was issued in 1993, when extensive research on the comfort women had not been conducted. Almost 50 years having passed since the end of WWII, the comfort women was a new enigma in 1993. The Basic Relations Treaty of 1965 also finalized any claim from Korea. So, the Statement, as well as a number of apologies before and after the Statement, was made for the purpose of easing the pain of the surviving Korean comfort women. Because of the Japanese government’s lack of clear grasp of the comfort women then, the Statement is apologetic, but its wording is ambiguous. It acknowledges (1) that wartime comfort stations were operated in response to the request of the military authorities of the time, (2) that the then Japanese military was, directly or indirectly, involved in the establishment and management of the comfort stations and the transport of comfort women to volatile war zones, and (3) that in many cases comfort women were recruited against their own will, through coaxing and coercion. The Statement intentionally leaves the agents or causes of coercion undefined because the circumstances for each woman were obviously diverse.

Now, we know that some Korean women were sold to brokers by their families; others were recruited by procurers with false promises of employment. Still others had multiple causes. In these cases, from the women’s point of view, their recruitment was coerced against their will. We also know that the majority of them volunteered to work as comfort women in order to pay down their families’ debts.

The Statement also makes an implicit reference to a well-known human right violation incident in which 11 Japanese soldiers and officers, defying the order from above, forced 35 Dutch women into sex slavery in Samarang, Indonesia, for two months in 1944. As soon as Lieutenant Colonel Kaoru Odajima flew into Indonesia from Japan and found about the case, he ordered to shut down the stations, and those involved in the incident were prosecuted after the war. The 35 victims were not comfort women but victims of sex slavery. The Samarang Incident, however, was already concluded with the prosecution of the involved, and the case has nothing to do with Korean comfort women.

Although the Statement has an inherent problem of linguistic ambiguities, it never acknowledges that the Japanese military systematically coerced women into prostitution, for there was no such evidence. The Statement’s linguistic ambiguities, however, along with the Japanese politicians’ apologies made before and after the Statement, were not only misinterpreted by many but also abused by some, who attributed the responsibility of “coerced” prostitution solely to Imperial Japan and promulgated the myth of sex slaves abducted by the horrendous Japanese military. The myth has further evolved itself recently, and now it goes “Approximately three-quarters of comfort women have died as a direct result of the brutality inflicted on them during their internment. “ This is a very serious allegation against the Japanese race.

In Korea’s Place in the Sun (2005), Prof. Bruce Cumings, a specialist in modern Korean history and contemporary international relations in East Asia at the University of Chicago, states that many women were mobilized (as prostitutes) by Korean men. There are also many documents that show that the Japanese authority was trying to control illegal human trafficking in the Korean peninsula.

Attachments 1 and 2 show that, far from being slaves, comfort women were well paid. Attachment 3, Army Memorandum No. 2197, explicitly prohibiting abducting or recruiting by using the army’s name, shows that the Japanese authority kept a watchful eye on illegal human trafficking in the Korean Peninsula. Attachment 4, a newspaper article, shows that the police in the Peninsula arrested Korean brokers who had cajoled women into prostitution by promising them extraordinarily high payments. Abundant evidence shows that Korean women were swindled, kidnapped, or sold by Korean brokers, not by the Japanese army. Abuse of women, rampant prior to 1910 annexation of Korea to Japan, unfortunately could not be eradicated from the Peninsula during the Japanese rule and is still continuing in Korea today. The last attachment, titled Japanese Prisoner of War Interrogation Report No. 49, is a U.S. Office of War Information report published in 1944; and it describes the living conditions of 20 Korean comfort women captured in Burma, present-day Myanmar.

I, as well as many Japanese and Japanese-American residents of California and Japanese tourists visiting Buena Park, would be deeply disappointed if Buena Park decides to build a memorial of comfort women by blindly believing the Korean activists’ theories without scrutiny. As a mother of two American citizens of Japanese descent, I am also concerned that my daughters would be unfairly and wrongfully disadvantaged by this kind of condemnation on their mother’s native land. I hope fairness and justice of yours prevail on the city’s decision as to whether a memorial of Korean comfort women should be erected in Buena Park. Thank you very much for taking your valuable time to read this long letter.

Sincerely,

Kazumi Takahashi Chino Hills, CA

、

490高橋和美様

米国在住の2児の母として格調高く、感動的かつ説得力ある素晴らしいletterを市長あてに発信されました。当然、他の議員や地元media宛てにもCCされたかと思います。日本の一部極右の意見などという誤解を解くためAll Japan、いや、良識ある米国人(テキサス親父など)からのメッセージも必要です。