韓国在住の日本人のお母様から、歴史問題が韓国の教育現場で子供たちに及ぼす影響と現状についてメッセージをいただきました。

日本は悪い国だからと、子供たちが経験する嫌がらせには心が痛みます。

最後に結ばれた言葉「日本に強くあって欲しい」を私たちは真剣に受け止めなくてはいけないと思います。

是非お読みください。

*********************************************************

2020年(令和2年)10月

親愛なる皆様へ

私は韓国の男性として結婚し今年で32年目になります。

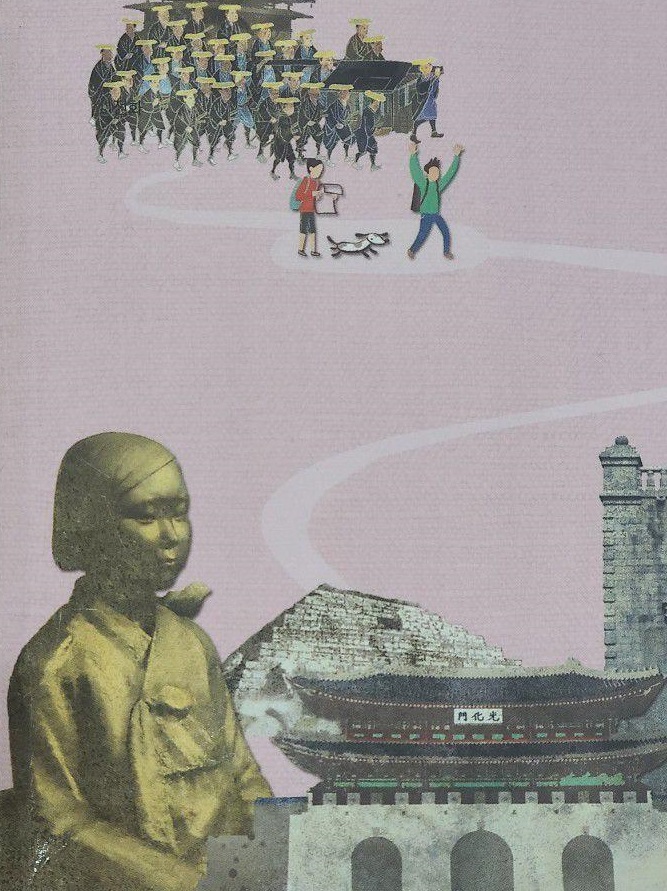

今回は日本と韓国を行き来する日本人女性として、今の日韓関係のいびつで根の深い歴史的問題とその結果学校の教育現場で実際子供たちが遭遇している嫌がらせについてお話ししたいと思います。

たぶん日本に在住の日本の方々は韓国の異常とも言える反日行動に嫌気がさし、縁を切りたいと思われている方もずいぶんいらっしゃるだろうと思います。

また一方では韓流ドラマやスターにひかれあまり実感のない日本人も多いことと思いますが、実際の韓国での子育の中で日本人の親(両親が日本人の場合は日本人学校に送るので例外ですが)を持つ子どもたちは非常に辛い体験をします。

昨年韓国と日本でベストセラーになった「反日種族主義」という本のなかにも書かれてありますように、韓国人の潜在意識のなかには著者の李栄熏先生が言及されたように「日本は常に悪玉で韓国はその日本から侵略され略奪され残酷なことをされた」というものがあります。

実際はそうではないのですが、もうそのように刷り込まれていて多くの人が嘘とは思っていません。

人によっても差はありますが、大東亜戦争もともに戦い同じ国民であったにも関わらず、自分達は戦勝国の一員と思っている人も多くいます。

大河ドラマや映画も日本統治時代を日帝時代と言いますが、その内容で作品をつくると人気が出て視聴率も上がるし、映画も収入が上がるのでたくさん製作されます。それは日本人が常に悪玉として出て拷問したり酷い仕打をするので、結局韓国国民はその芸能作品を通して歴史の勉強をしていると言っても過言ではありません(嘘の歴史)。

もちろん人間的には良い方もいらっしゃるし、仲のいい友人もたくさんいますがその観念は意識の根底にあるのです。

長男が小学校に通っているとき(1990年代)そのような連続ドラマがある翌日には私の息子たちが学校に行けば「どうやって責任をとるんだ?」とクラスの生徒も先生たちからもからかわれました。

また母親が日本人ということから喧嘩が始まり息子の手の甲の骨が完全に折れたままで学校の授業が終わるまで何ら気にかけてももらえず、家に帰って病院につれて行ったとき、レントゲンを見てヒビが入るどころかポッキリ折れていることがわかりました。(手術をし入院)

担任の先生からも何らお話も説明もなく、相手の親からも何ら連絡はありませんでした。

息子はそのとき何故喧嘩したのかという理由を言わず、ただの喧嘩だと思っていましたので主人も男の子だからとそのままでした。(数年後に告白しびっくりしました)

学校の近代史の授業になると先生が燃えて日本人の蛮行を講義すれば他のクラスメートは息子の方を見て「日本人を殺さないといけない」と言ったりして、「お母さん今日も先生日本の悪口言ったよ」と話たことを覚えています。

ただそのとき私自身が自虐史観であったことと主人も日本がそうだったから仕方ないと言って、息子の心の傷を親として癒してあげれなかったことは本当に反省しています。

四男も「チョッパリ」(豚の足で日本人が当時履いていた足袋のことです)と言われ泣いたこともあり、とにかくお母さんの名前で学校から送られるプリントにサインしてほしくないと言っていました。

4人の息子も成人し、これからこのように私の息子たちが体験したことを繰り返してほしくないと思っていましたが、最近は現政権になり学校の教科書自体がさらに左傾化していています。

慰安婦問題はもちろん、片親が日本人(母親が多い)だと子供たちは自分の母親が日本人だということを隠します。

私の後輩で韓国の夫を持つ日本女性ですが、息子さんの中学校の卒業式に「お母さん来なくてもいい。来るな。」と言われ行かなかったそうです。

また別の後輩は娘さんが小学校で授業中に「自分の好きな国の国旗の絵を描く」というテーマがあって、その娘さんは自分のお母さんの国の国旗「日の丸」を描きました。が、その娘さんの絵だけ教室の壁に貼られなかったとのことです。

お母さんが先生に聞いたところ、「日本が憎いから」と言われたそうです。

教科書には日清戦争や日露戦争のことも記述してありますが、ただ日本の帝国主義の侵略、大東亜戦争も日本の侵略戦争、徴用工や慰安婦の強制連行や南京大虐殺等、記述してあります。731人体実験も信じてます。

このように韓国の近代史は日本悪玉論の色で塗られています。このような本で勉強すれば反日にならざるを得なく、憎悪心はあらゆる所に現れてきます。

昨年、日韓関係が最悪状態になった時期、徴用工判決(戦時労働者ですが)慰安婦問題、レーダー射撃、文国会の議長の天皇陛下侮辱発言、芸能人の原爆Tシャツ事件を見ても日本人としては耐えられない侮辱感を感じられたかたはほとんどだと思います。

この時、韓国国内は何とも感じず言論はすり替え論一辺で国民もそれに流されている異常な状態でした。

私は特に日本で経済活動もし、ファンも沢山いる某少年グループの原爆Tシャツ事件で大ショックを受けました。

犠牲者の何十万という日本人そしてその中には朝鮮の人もいました。でもそれを平気で着ていて何ら罪悪感を持たないという心理状態は75年間にわたる韓国の反日教育、教科書が元凶だとしみじみと実感しました。(それに問われない日本好きの人も中にはいますが)

このめちゃくちゃな教育のゆえ、心の傷を負った子供たちは放置されたままです。

韓国の国内もSNSの発達で李氏朝鮮時代や日韓併合時代の真実を知りつつある人も増えていますが、まだまだわずかでほとんどが歪曲された歴史を鵜呑みにしていると言っても過言ではありません。

その良識的な少数の韓国人は、日本に強くあって欲しいと願ってます。

以上