独ベルリンの新聞社 Berliner Zeitungの10月13日付記事で、慰安婦像についての記事が掲載されました。

Berliner Zeitung 2020年10月13日 Hanno Hauenstein

Friedensstatue: „Historische Amnesie und Zensur“

平和の像:„歴史の記憶喪失と検閲”

https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/kultur-vergnuegen/berlin-entfernt-friedensstatue-historische-amnesie-und-zensur-li.111137

日本語訳 をご紹介します。

*****************************************

Berliner Zeitung 2020年10月13日

平和像:「歴史的な記憶喪失と検閲」

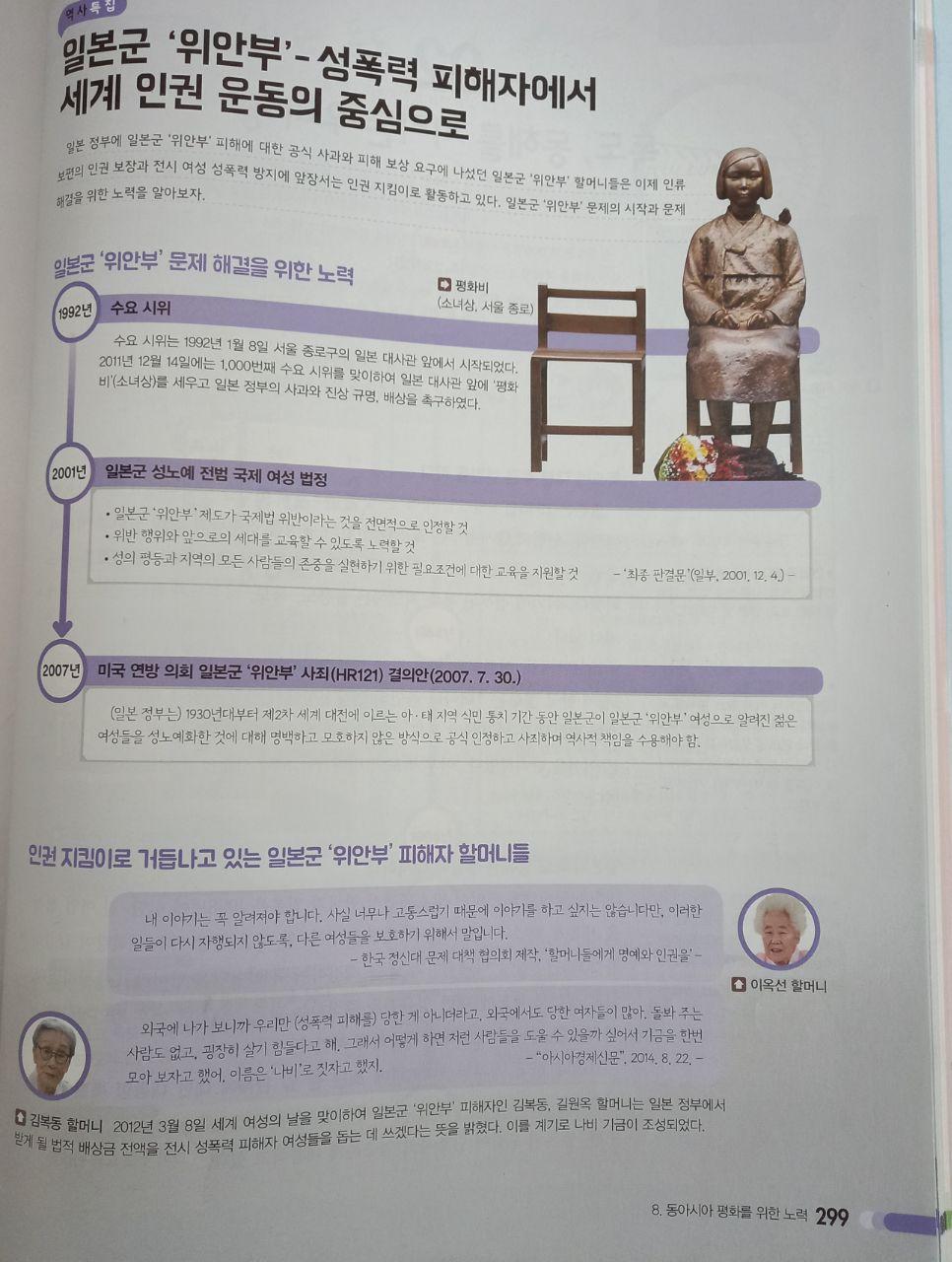

キム・ソギョンとキム・ウンソンの平和像は、女性に対する性的暴力を想起させます。 モアビットでは、芸術作品の一つが日本からの圧力によって取り除かれることになっています。それは間違いです。

写真:アーティストのキム・ウンソンとキム・ソギョン 2019年秋の展示会オープニングにて プラスティック版の平和像とともに 出典:コリア協会

ベルリン-世界中の活動家達が植民地時代の像を標的にし、わずか数ヶ月が経ちました。現在ベルリン・モアビットで行われている記念碑政策論争で、アーティスト夫婦のキム・ソギョンとキム・ウンソンによる「慰安婦」の平和の像は、陰で形勢が逆転しています。活動家は彼女(像)を邪魔しませんが、邪魔するのは政府、より正確には日本です。 そしてベルリンは屈服。 平和像には歴史的な不正は見られません。 いいえ、彼女には一つ思い当たることがあります。 東京がこれを認めたくないということだけです。

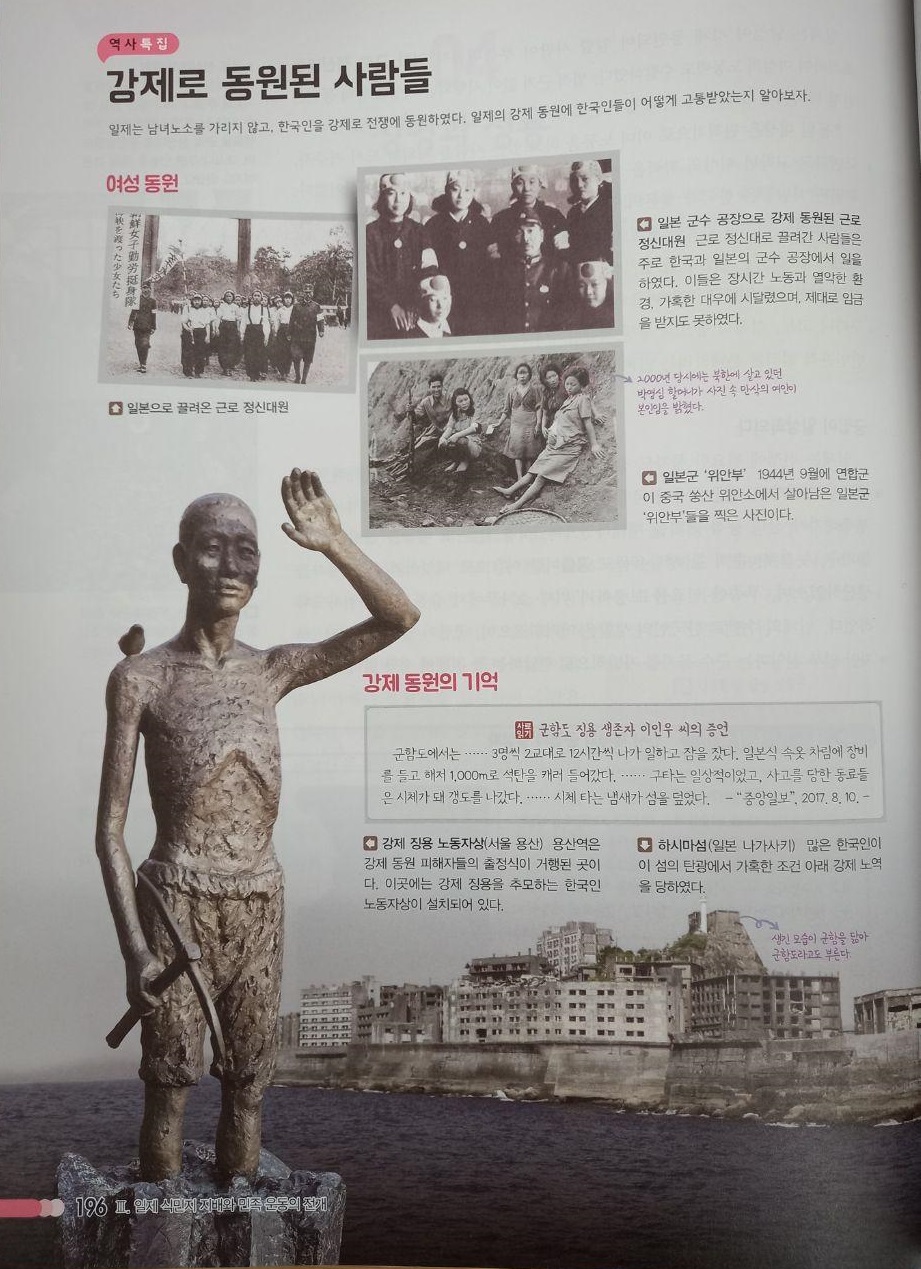

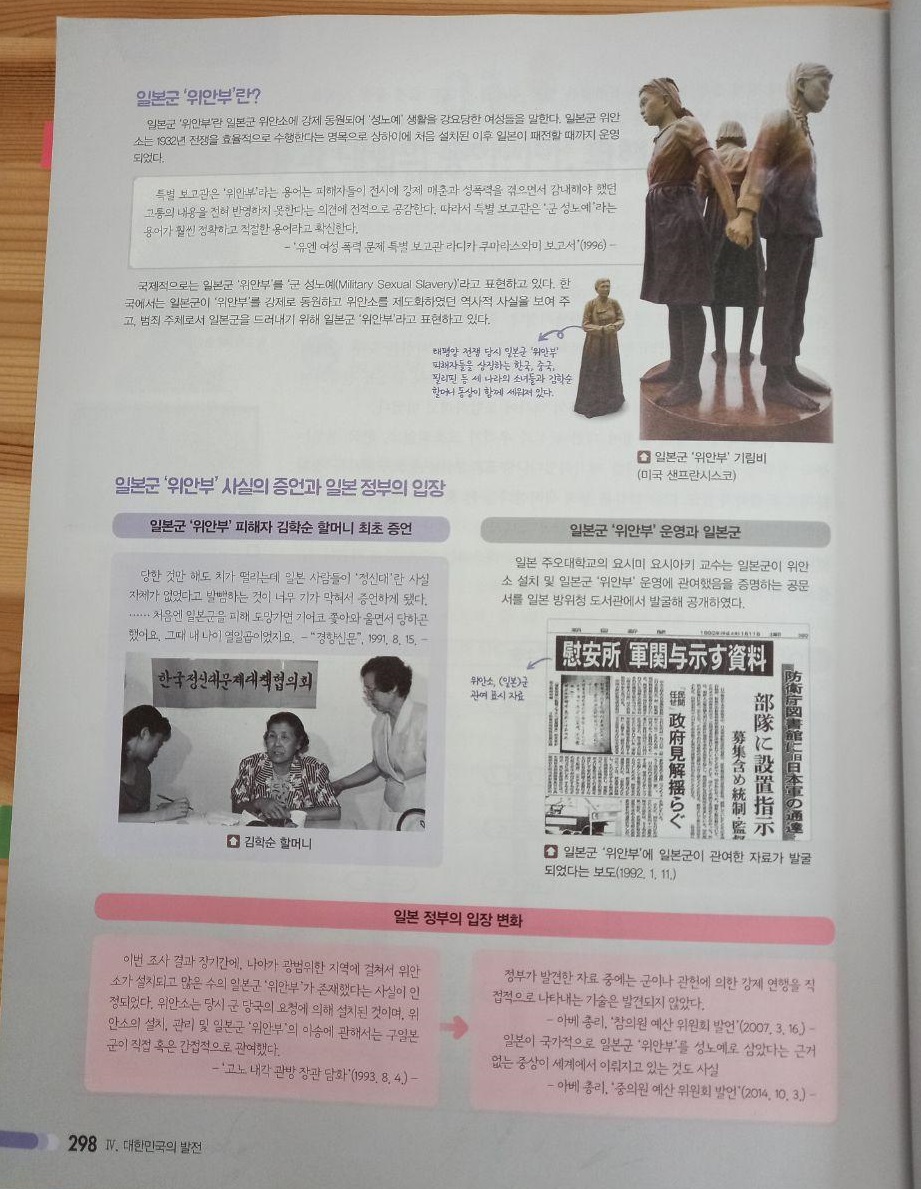

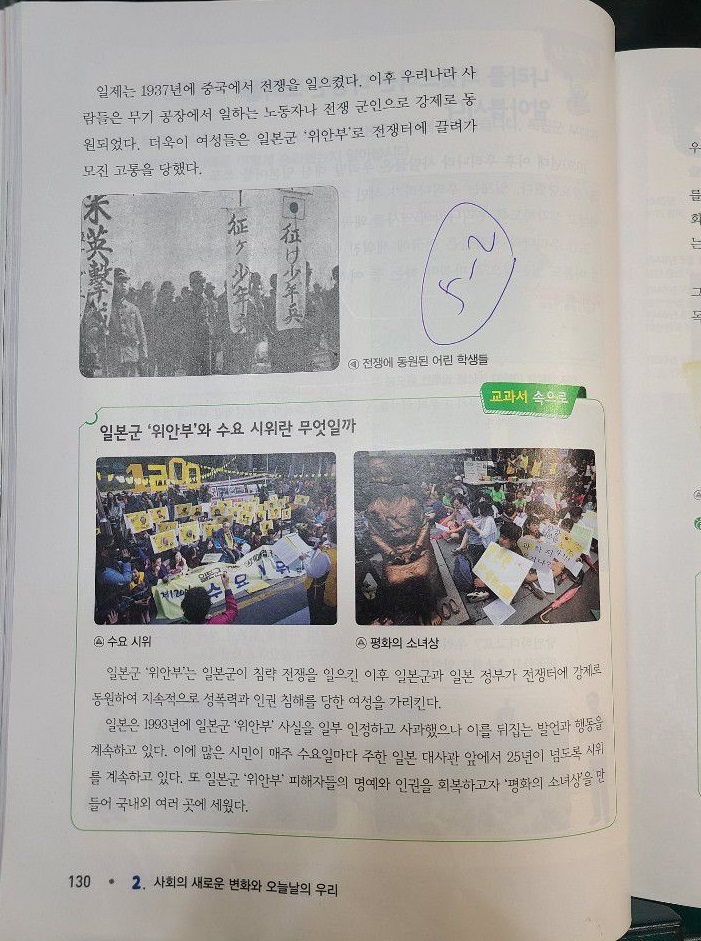

それは欺瞞的な婉曲、「慰安婦」という言葉の中に隠されているのは : 11歳から19歳までの若い少女達と女性達は、第二次世界大戦中に日本が占領した地域で売春を余儀なくされました:「性奴隷」だと、ちょっと衝撃的に聞こえますが、その問題にはより適切な言葉です。

長い間日本のナショナリストにとって平和の像は、目の中のトゲです。「それを解体することは歴史の記憶喪失と検閲です」と語るのは、ベルリンを拠点とするアーティスト、クリスタ・ジュヒョン・ダンジェロで、彼女自身が彼女の作品で日本の帝国主義と性的暴力に取り組んでいます。「女性達の多くは家族によって沈黙させられました。 そのテーマは非常に恥ずべきことでした。そのためようやくここ数年で光が当たったのです。」

日本からの圧力は大きい: 2019年、東京(記者の間違い、正しくは愛知)のアートメッセで平和の像を展示する展示会が突然終了しました。2017年、レーゲンスブルク近郊の平和像の説明パネルは、日本大使館からの圧力を受けて撤去されました。2018年、大阪はサンフランシスコとの姉妹都市を終了しました。サンフランシスコは似た様な像の撤去を拒否したためです。 ウィキペディアのエントリ「Statue of Peace」でさえ、現在撤去の脅威にさらされています。

「ミッテ地区役所は、東京を気に入られるために薄っぺらな疑似議論を構築している。」と、ベルリンの政治について、コリア協議会のナタリー・ジョンファ・ハン代表は述べました。 ハイコ・マースも間接的に批判されています。 ベルリン上院には、見直す事が期待されています。 正しい方に。

アーティスト夫婦の像が外交関係を揺るがすだなんて、二人はおそらく想像することができなかったでしょう。

*****************************************