慰安婦像設置計画が進んでいるフィラデルフィア市。賛成・反対両者のからの意見を参考にするために、まだ最終決定されていません。

皆様からもご意見是非送ってください。

ご参考に、AJCN(オーストラリア-ジャパン・コミュニティ・ネットワーク)からフィラデルフィア市長に宛てた、慰安婦像設置に反対する手紙をご紹介します。

※フィラデルフィアに意見を送る方はこちらのメアドとリンクを参考にしてください。

・フィラデルフィア市

city.rep@phila.gov

・フィラデルフィア市議

darrell.clarke@phila.gov

mark.squilla@phila.gov

kenyatta.johnson@phila.gov

jamie.gauthier@phila.gov

Curtis.Jones@phila.gov

maria.q.sanchez@phila.gov

cindy.bass@phila.gov

Cherelle.parker@phila.gov

brian.oneill@phila.gov

・フィラデルフィア市芸術局

arts@phila.gov

・フィラデルフィア市長コンタクトフォーム

https://www.phila.gov/departments/mayor/mayors-correspondence-form/

***************************************************************

March 9, 2022

Mr Jim Kenney,

The Mayor of Philadelphia

Re: The installation plan of “Statue of Peace” in your city

My name is Sumiyo Egawa, a Japanese resident of Sydney, Australia, and the President of the Australia-Japan Community Network (aka AJCN). AJCN is a small volunteer group of Australian and Japanese parents concerned about the safety and security of our children living in Australia.

I am extremely saddened to hear about your plan to install an art object, the so-called “Statue of Peace,” in your city. I object to the proposed project for the following five reasons.

- “Statue of Peace” cannot be classified as art

There are at least a dozen similar statues in the US alone, some in Europe and almost fifty in South Korea.[1] Statues of Peace have no originality, and manufacturing the statues has been a lucrative business for the Korean couple sculptors Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung. They have duplicated the original Comfort Woman statue or similar ones since 2011.

- Korean Activists Use “Statue of Peace” for the purposes of Japan Discounting and Bashing

In the case of the “Statue of Peace” in Glendale in 2013, Glendale Mayor Dave Weaver was not sufficiently informed of the script’s content upon the Statue, before it was constructed. Later, the Mayor issued a letter of regret about Comfort Women Memorial.[2] The engraved fabricated message unfairly targeted and condemned Japan, and Japanese soldiers, who fought during WWII. On the other hand, the inscriptions conceal Korean soldiers’ atrocious behaviour towards Vietnamese women during the Vietnam War, resulting in the births of many Korean-Vietnamese children, known as Lai Dai Han.

- Anti-Japan Romanticism is known as Han-Nichi in South Korea

A few years after WWII ended, successive Korean governments used negative Romanticism for its political advantages and propaganda against Japan. The Korean education system implanted the Anti-Japan mindset within Korean children’s tender minds. This phenomenon is openly explained in the book “Anti-Japan Tribalism,” written by the six Korean academics, published in 2019.[3] This book is written in the Korean language to inform ordinary Koreans of the truth about Comfort Women.

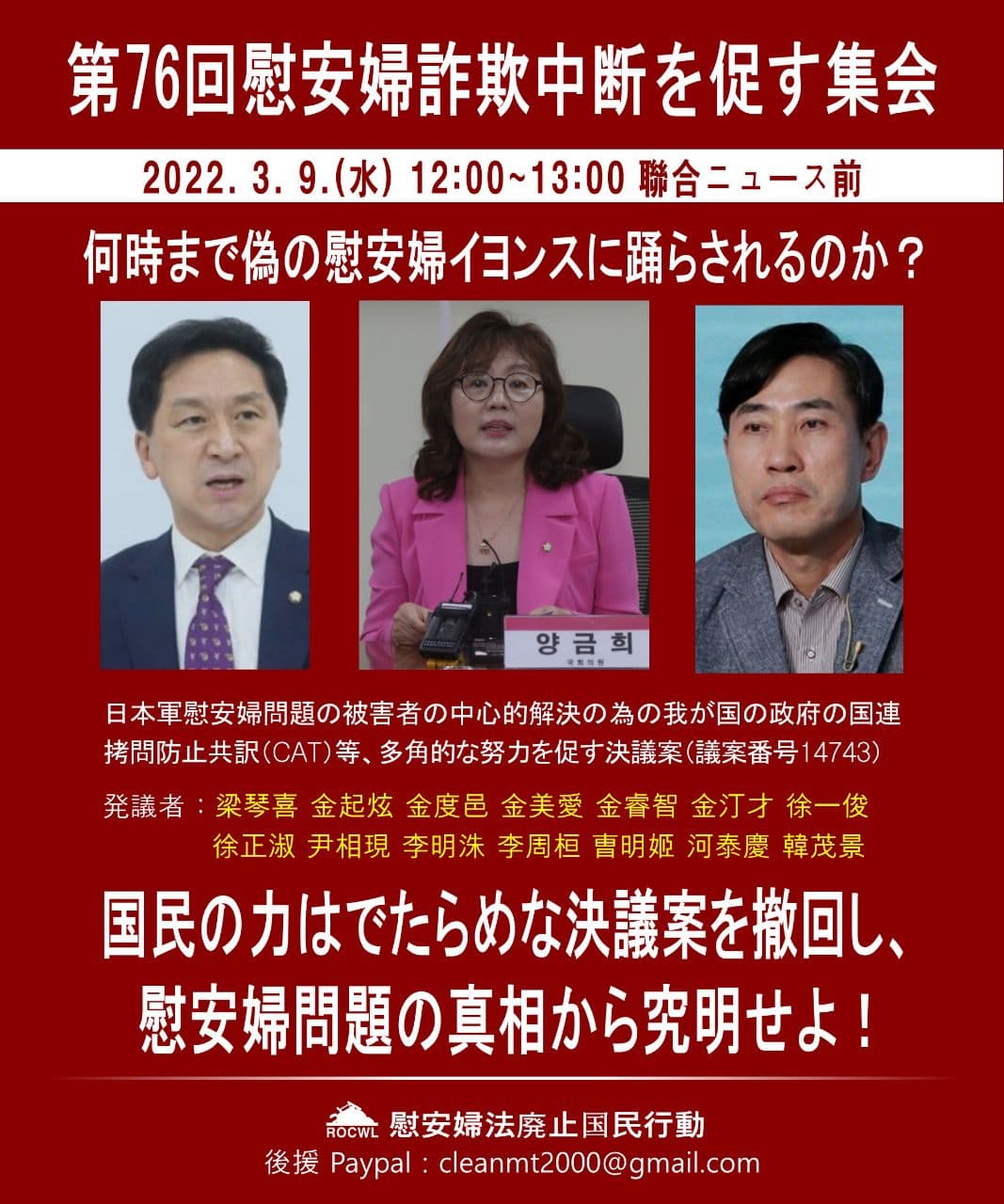

- The mini-battle field of For and Against Comfort Woman Statue in Seoul

Since the first statue was built in Seoul in 2011, opposite to the Japanese Embassy building, the Anti-Japan campaign has intensified. Since 1992, the so-called “Wednesday Demonstration” has been conducted in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul Korea, every Wednesday, and organizers collect donations. However, after the publication of “Anti-Japan Tribalism,” many enlightened Korean youths led by Professor Lee Woo-yeon have counteracted and confronted against Anti-Japan activists at the same spot, face to face.[4] Although the Japanese Embassy has re-located, the surrounding area of the Statue remains as a mini battle field between For and Anti Comfort Woman Statue advocates. A similar movement occurred in front of the Japanese Consulate in Sydney every Wednesday. However, since the Korean activists failed to set up a Comfort Woman Statue in the Sydney suburb of Strathfield in 2015, such activities faded away and eventually halted.[5]

- Korea’s claim about Comfort Women as Sex Slaves is a malicious lie

On December 1, 2020, the American Legal Scholar, Professor J. Mark Ramseyer at Harvard University, published the well-researched paper, “Contracting for sex in the Pacific War,” explicitly explaining that Comfort Women were not Sex Slaves but wartime prostitutes during WWII.[6] Various primary sources support Ramseyer’s paper. Nevertheless, Ramseyer was viciously and emotionally attacked, and labelled a history revisionist by Korean supporters. Ramseyer had called for written dissents from critics, but only a very few responded to Ramseyer’s request. Recently, Ramseyer has written and published a paper, “CONTRACTING FOR SEX IN THE PACIFIC WAR; A RESPONSE TO MY CRITICS,” in which he demonstrated his research’s authenticity.

Briefly, I have explained the background and hidden agendas behind the “Peace Statue,”

and I am sincerely asking you to acknowledge that Philadelphia has no relation to Korean War Time Prostitution. Please reconsider building a false statue, which will bring no peace and happiness, but create negativity and hurt. Such negativity is unnecessary and creates unprecedented conflict within your community, as well as sending biased information about Japan to young children. Accordingly, Philadelphia is not a suitable place to display a “Peace Statue” in a public area. The Statue will not bring peace and harmony into your city, but hatred, division and unnecessary trouble. Philadelphia does not need such a negative monument.

Thank you for your kind attention to my letter.

Yours faithfully

Sumiyo Egawa

President of AJCN

http://jcnsydney-en.blogspot.com/

[1] Ward Thomas D. & Lay William D.”World II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States,” E-International Relations Publishing, 2019.

https://www.e-ir.info/publication/park-statue-politics-world-war-ii-comfort-women-memorials-in-the-united-states/

[2] Brittany Levine. “Mayor Dave Weaver’s letter states regret about “Comfort Women” Memorial.” News-Press,

November 2, 2013. https://www.latimes.com/socal/glendale-news-press/news/tn-gnp-xpm-2013-11-02-tn-gnp-me-letter-20131102-story.html

[3] Lee Yong-hoo, Joung An-ki, Kim Nak-nyeon, Kim Young-sam, Ju Ik-jong and Lee Woo-yeon. “Anti-Japan Tribalism.” Tokyo: Bungeishunjū, 2019.

[4] “South Koreans grapple with convention-busting bestseller on Japan.” NIKKKEI Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-South-Korea-rift/South-Koreans-grapple-with-convention-busting-bestseller-on-Japan

[5] The Strathfield Council members voted against the construction of the Comfort Woman statue in the public arena. Australia is a multicultural society and values peace, harmony and tolerance. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/threats-insults-and-tyres-slashed-in-strathfield-over-comfort-women-memorial-20150814-giz7ri.html

[6] Ramseyer, J.M. “CONTRACTING FOR SEX IN THE PACIFIC WAR; A RESPONSE TO MY CRITICS.”

Harvard Law School John M. Olin Centre Discussion Paper No. 1075, February, 2022.

Ramseyer, J.M. “Contracting for sex in the Pacific War.” International Review of Law and Economics 65(2021) 105971, December 1, 2020,