Miroslav Marinov, Ph.D.

Toronto, Canada

December 7, 2020

An Herrn Bezirksbürgermeister

Stephan von Dassel

Mathilde-Jacob-Platz 1

10551 Berlin

GERMANY

bezirksbuergermeister@ba-mitte.berlin.de

An Open Letter Regarding the “Peace Statue” in Berlin Mitte District

Sehr geehrter Herr Bezirksbürgermeister,

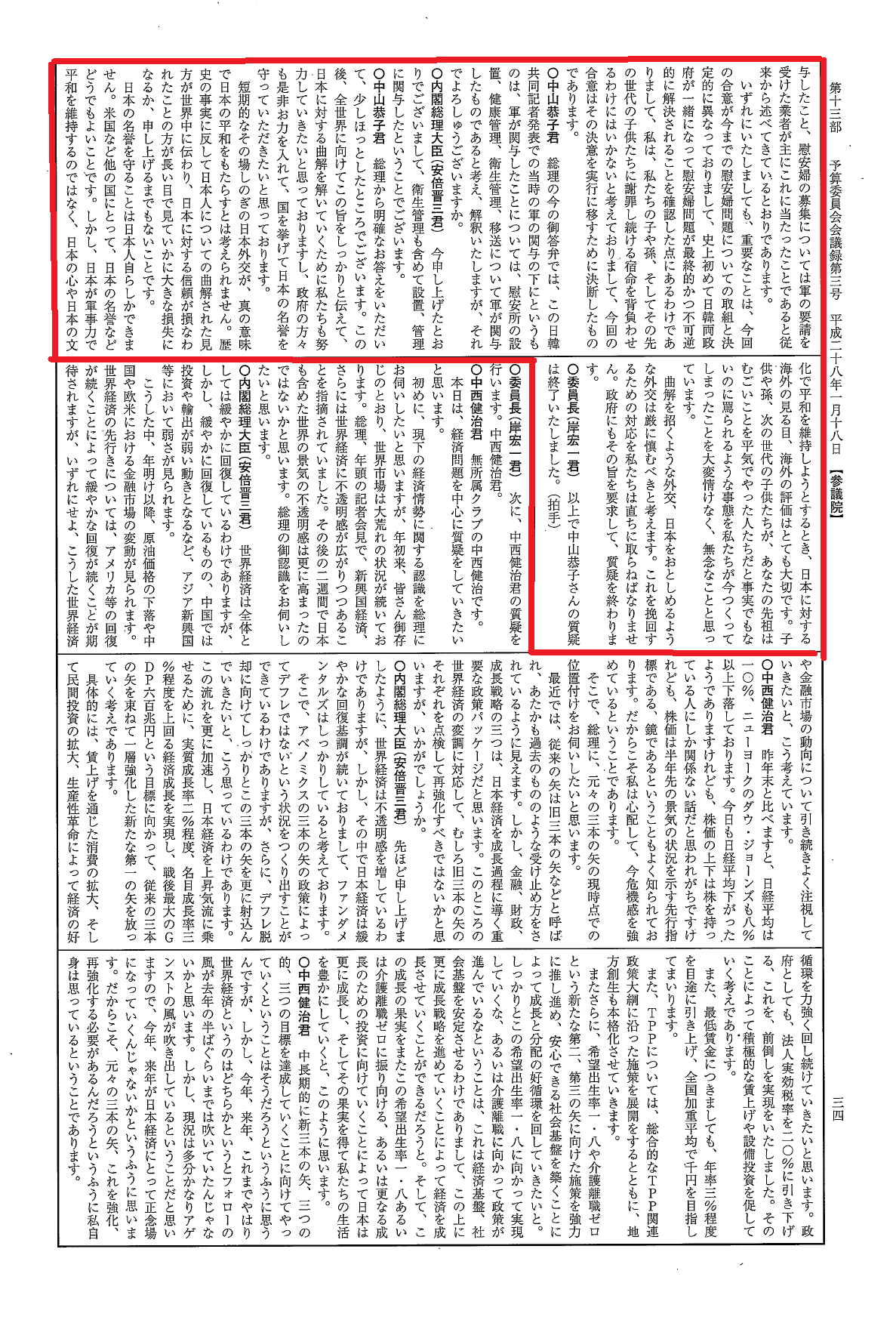

I am writing to you regarding the controversy that erupted in Berlin after installing a “Peace Statue” commemorating the so-called “comfort women”. My name is Miroslav Marinov, and I am a Canadian writer and researcher who specializes in the history of World War II and specifically the Holocaust. For years, I have conducted research on those issues in Canada, Israel, Poland, Japan, South Korea, China, Singapore, Russia, and the former Soviet Union.

The main function of a municipality is to make sure that the local residents receive services necessary for maintaining and improving their quality of life. Obviously, your offices also provide safety and maintain the peace in your district. Just like Toronto, Berlin is a multicultural city where people from many ethnicities and religious backgrounds are expected to co-exist in peace.

From that point of view, any involvement of the local authorities in inter-ethnic controversies requires sufficient knowledge of the underlying issues, especially when they involve decades of history. That should include the “Peace Statue” as well, which may be seen in Europe as another memorial of little importance, but it is something that would cause an ideological firestorm in the Far East.

Although Mitte District (“Bezirk Mitte”) has been involved in the issue, I am not aware of any official statement of the municipality for or against the statue.

From my research of the materials in the German press, it seems to me that the arguments of the supporters of the statue have been best expressed in a long article published in Moabit Online ( https://moabitonline.de/35307 ) under the title “Little Girl – Big Swirl: Japanese militarism at our doorstep” (“Kleines Mädchen – großer Wirbel: Japanischer Militarismus vor unserer Haustür”). Its author was Mr. Andreas Szagun who teaches history at Berlin Mitte Adult Education Center (“Geschichte an der Volkshochschule Berlin Mitte”). He also authored an open letter to you, which was quoted in full in the comment section of the article. His interest in the issue stems in part from his activism in the peace movements since the 1980s, as he states in the letter. For your information, I can read German, but writing in German would be time-consuming, that is why I am writing this in English, for which I apologize.

Since Mr. Szagun’s arguments may influence your decisions, I would like to address them, especially those that need to be questioned with more facts. So, there will be many historical facts covered in this letter. While many people in the West find history boring, there is no way to escape it if one wants to form an opinion on issues that concern distant parts of the world.

The main obstacle to objectivity in exploring the turbulent years preceding World War II and the war period as well, is the strong Eurocentric approach, which has not changed since the 1940s. While this seems to have a lesser effect on evaluating European history, it significantly distorts the interpretation of the Far Eastern history and its modern-day fallout.

For starters, Mr. Szagun contrasts the “vile, horrid” side (“garstige Seite”) of Japan with its image as a “Land of Smiles” (“Das „Land des Lächelns“”). Japan has never been known as a “Land of Smiles”. This expression is a “trademark” of Thailand. Any visitor will be reminded about it at every hotel in Bangkok and at any tourist trap during a group trip.

As of the major issues, it has been a “tradition” to lump into the same category all countries that were on the side of Germany during World War II. Mr. Szagun does not miss this opportunity, as he writes: “The cult around the Tenno, the Japanese emperor, can be compared with the Hitler cult in this country. However, with one big difference: the current Tenno is considered godlike in Japan’s own Shinto religion.” (“Den Kult um den Tenno, den japanischen Kaiser, kann man dabei durchaus mit dem Hitlerkult hierzulande vergleichen. Allerdings mit einem großen Unterschied: Der jeweils amtierende Tenno gilt in der Japan eigenen Shinto-Religion als gottgleich.”)

The superficial comparison between Adolf Hitler and the Japanese Emperor was an important tool in the Allied wartime propaganda. Similar denigration we find in the writings of Nikolai Bogdanov, a prominent military correspondent from the USSR sent to Japan to cover the surrender ceremonies in 1945, who wrote: “The Emperor Hirohito – self-important, pouty and decorated like a peacock. The Japanese believe that he is the “Son of Heaven”, divine incarnation on earth.” [1]

Mocking the Emperor cannot hide the historical context. Hitler was a leader of a social movement that became popular and eventually came to power due to the negative consequences of World War I for Germany. Its core idea was the Aryan racial superiority, which, after the initial declared goal of unification of the German territories in the late 1930s, fueled a war for expanding the “Lebensraum” of Germany.

In contrast, the institution of the monarchy in Japan preceded Hitler by over 1,300 years, with an uninterrupted royal lineage. Throughout Japan’s history, the imperial institution has had its ups and downs – from strong power to an extremely limited influence during the shogunate. Only one thing was constant, the Emperor was always the symbol unifying the nation and yes, he had a divine status. This may seem ridiculous from the point of view of the “enlightened” West, but many nations hold similar views about the order in their countries, but they are rarely, if ever, criticized.

Unlike Germany, which was a totalitarian dictatorship under Hitler, Japan had a functioning parliament, with political fights and confrontations. Another important but often ignored point is the treatment of the Jews. Hitler was notorious for his anti-Semitism – in “Mein Kampf” the ultimate villain who “controlled” and “destroyed” the civilized world was “The Jew”. The horrific consequence of that view was the mass extermination of the Jews in Europe, which became known as the Holocaust.

On the other hand, Japan never had any anti-Semitic policies. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan proposed the inclusion of principle of racial equality in the statutes of the League of Nations: “The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.” The proposal was rejected by the Western nations.

In 1920, Ambassador Keishiro Matsui, representing Japan at the San Remo conference of the League of Nations, signed the documents that created the Mandate for Palestine, where the future Jewish state was to be created.

Hitler’s takeover in Germany and his initial campaign of expulsion of the German Jews, soon affected Japan. In September 1935, Tadakazu Kasai, a Manchukuo consul in Manchouli, Inner Mongolia, issued hundreds of visas to German Jews who arrived through the Soviet Union. At the time, Manchuria was a puppet state, which followed the policies of Japan.

In Harbin, Manchuria, Japan had to deal with people of several ethnicities and their confrontations, especially clashes between anti-Semitic Russian immigrants and Jews. Colonel Yasue, who dealt with the Jewish issues, helped to overcome the confrontation. In 1936, he shut down the anti-Semitic Russian newspaper “Nash Put” (Наш путь – Our Path). The leader of the Harbin Jews, Dr. Abraham Kaufman, called him a true friend of the Jews and reliable defender of their interests in Tokyo. In 1941, Col. Yasue was inscribed in the Golden Book of the Jewish National Fund for his services to the Jewish People.

Also in Harbin, from 1937 to 1939, three conferences of the Jewish communities in the Far East were held with the participation of the Japanese government, which hoped to attract more Jews in order to develop the resources in Manchuria. The Japanese military authorities promised to support Jews in Manchuria in the spirit of their policy of ethnic equality.

In March 1938, about 20,000 Jewish refugees trying to escape Nazi persecution had arrived via the Trans-Siberian Railway on the Soviet side of the Manchurian border and were refused entry by the government of Manchukuo. Dr. Kaufman visited General Kiichiro Higuchi, of the Japanese army’s Harbin special mission department, and asked for help. Gen. Higuchi arranged for 13 trains to transport the Jews across the border. It is worth noting that at the Evian Conference the same year, where over 30 countries gathered to find ways to protect Jews from the worsening persecutions in Europe, not a single participant (other than the Dominican Republic) agreed to accept Jewish refugees.

In December 1938, a few weeks after the Kristallnacht atrocities in Germany, Japan’s top five cabinet ministers issued a declaration to protect Jews. The Jews living in Japan, Manchukuo, and China were to be treated equally with other foreign nationals and when arriving in Japan, the general regulations for admitting foreigners would be applied.

Meanwhile, in Shanghai in 1939, the flow of Jewish refugees from Europe was increasing. Japan, which had a concession in Shanghai, occupied the city in 1937, and by 1939 had complete control over it but did not change its visa-free status and did not interfere with the other administrative units, the British-dominated International Settlement and the French Concession. Thousands of Jews flocked into the city and, by the end of 1939, they were expected to exceed 30,000. Over 90% of the Jews in Shanghai, about 15,000, settled in the Japanese sector, where housing was more affordable.

Due to overcrowding, the Western authorities and the older Sephardic Jewish community, led by Sir Victor Sassoon, pressured Japan to introduce restrictions assuring it that the measure would not be perceived negatively by the world Jewry. Japan reluctantly agreed with the proposal to introduce US $400 fee for new arrivals, but that was applied only by the International Settlement. The fee was not adopted in the Japanese sector, every application was to be evaluated on its merits.

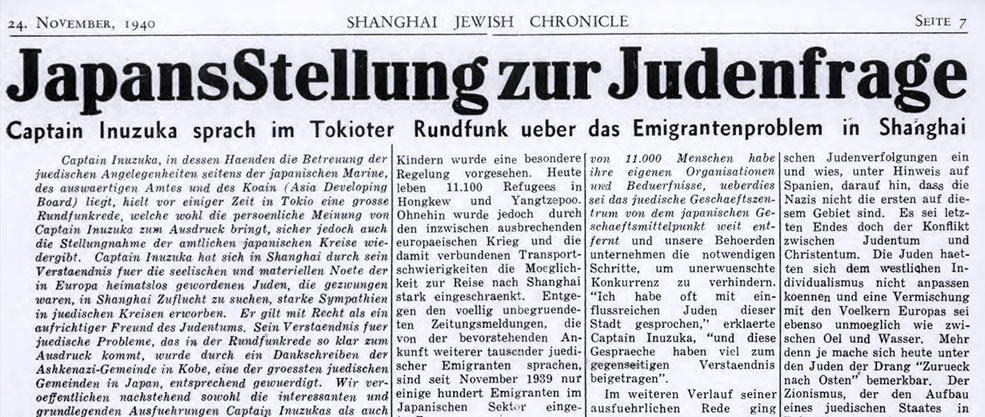

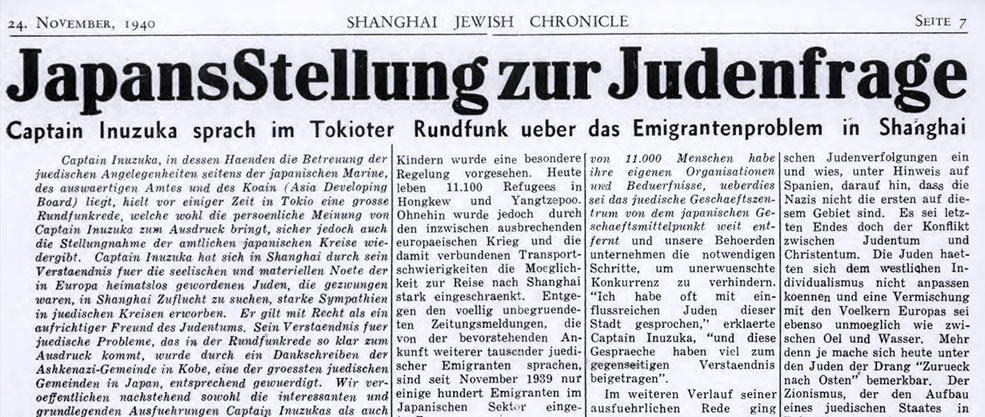

In November 1940, Navy Captain Inuzuka, one of the Japanese officers in Shanghai who dealt with the problems of the Jews, delivered a radio address on the Jewish refugee situation in Shanghai. He acknowledged the Jewish persecution in Germany, which had forced thousands of Jews to leave with only 10 Marks in assets. He praised their industriousness that brought many new businesses to Shanghai and pointed out the similarities between Jews and Japanese – both were Asian peoples that did not fit in the European individualism. He praised the Zionist movement that he hoped would bring them “back to the East” after Jews establish their state in Palestine. A detailed article covering his address was published in “Shanghai Jewish Chronicle” on November 24, 1940 – “Japan’s Position on the Jewish Question” (“Japans Stellung zur Judenfrage”):

Jews were also accommodated in the Japan-occupied Tianjin. Despite the claims of People’s Republic of China that China saved the arriving Jews, the country was way too dangerous to foreigners due to the ongoing civil war between Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalists, Mao Zedong’s communists and countless local warlords.

By mid-1940, the only way out from Europe was through the Soviet Union. The Russians allowed passage through their territories for people with transit visas. In May 1940, Chiune Sugihara, an intelligence officer from Japan’s Foreign Ministry, opened a consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania. There were no Japanese in the area, and Sugihara’s goal was to collect intelligence about a possible conflict between Germany and the Soviet Union.

At the time, thousands of Jews who fled Poland were stranded there, unable to leave Lithuania because they lacked visas. Lithuania was in its last months as an independent country. The Dutch Consul in Kaunas was willing to help them by issuing fictitious visas to the Dutch Caribbean possession of Curacao, but they still needed transit visas from Japan to be allowed to cross the Soviet Union.

The Jews approached Sugihara to request visas and he contacted the Foreign Ministry, which refused to give a permission a few times, but he started to issue transit visas, valid for 10 days in Japan. The bureaucracy was concerned about handling so many destitute people arriving in Japan. Eventually, Japan’s Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka (later indicted as a “war criminal”) agreed that Japan should honor the issued visas to keep its credibility though he still insisted that the consul adhere to the visa rules.

During his short stay in Kaunas, interrupted by the Soviet invasion, Sugihara managed to issue over 2,500 transit visas. In the final days before his departure, after the Russians shut down his consulate, he issued many blank visas, which were technically invalid. After Japan sent back to Vladivostok a ship with over 70 refugees with such visas, the Russians threatened to detain the Jews, so Japan took them back despite the irregularities. After that, all refugees were accepted.

Once in Japan, the destitute refugees were helped by the older Jewish communities in Kobe and Yokohama. The government facilitated the delivery of aid from the Western countries. Japanese people also provided food and shelter. Since the final destination was fictitious, most refugees had to stay much longer in Japan than the 10 days allowed by the transit visas.

People with connections to the government, like the Hebrew scholar Setsuzu (Abraham) Kotsuji used their influence to help the refugees. He contacted his former boss at the Manchurian Railways, Foreign Minister Matsuoka, with a request for help. Matsuoka suggested that Kotsuji approach the local authorities who had jurisdiction over the visa extension and ensured him that the Ministry would not interfere, so, the visas were often extended for many months.

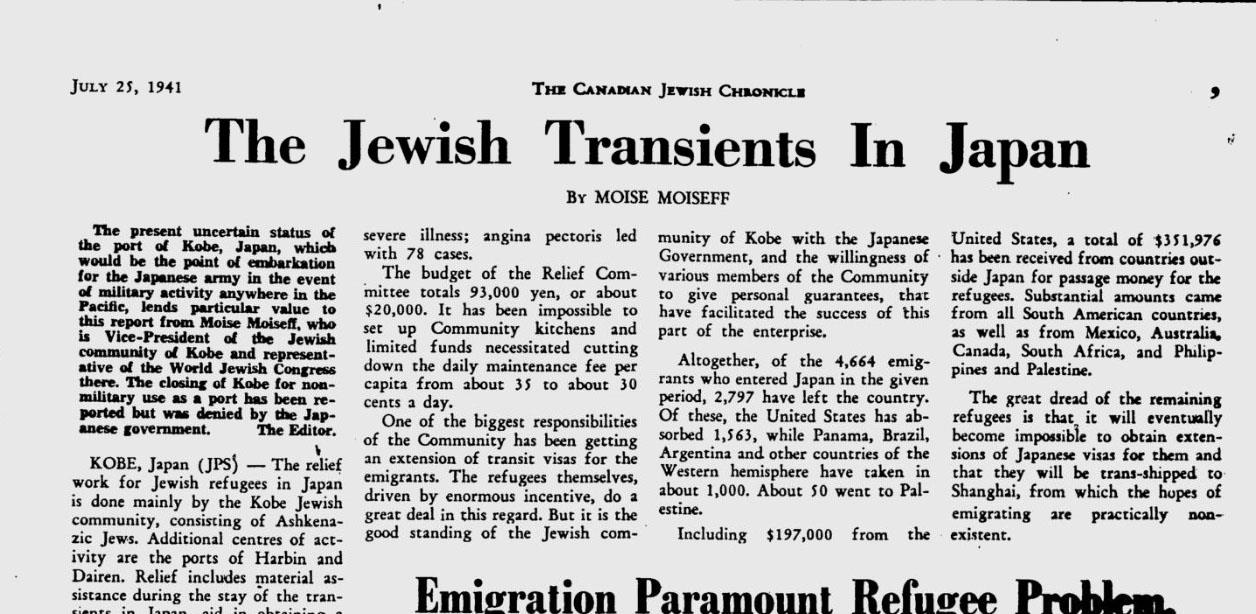

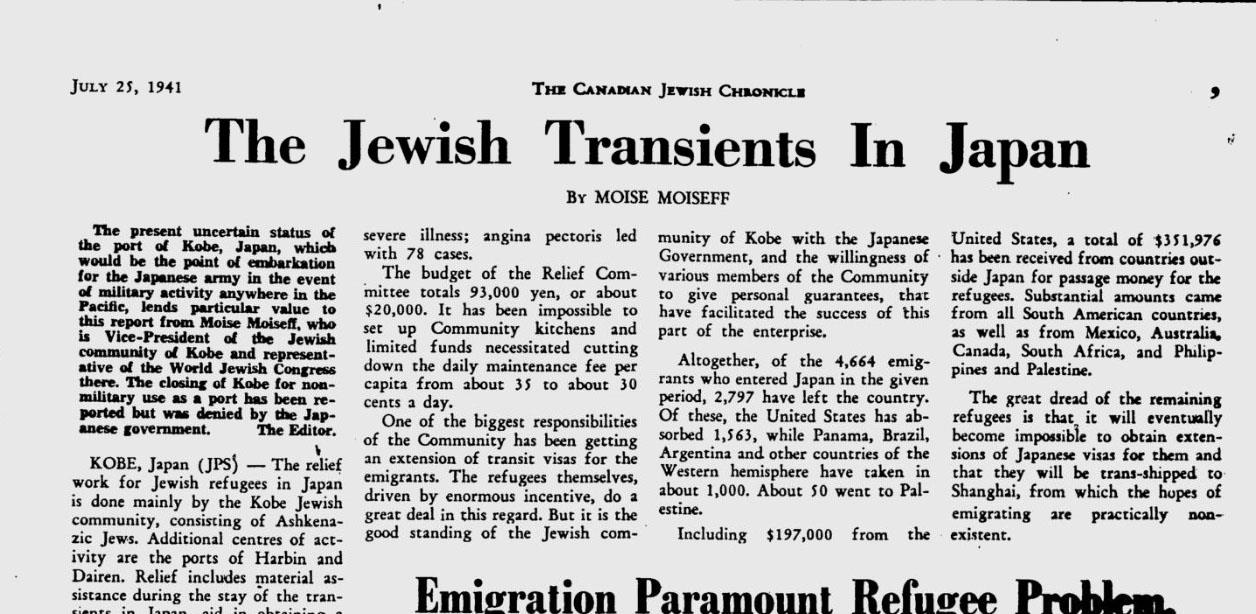

Here is a report about those refugees, which appeared in “The Canadian Jewish Chronicle” in the July 25, 1941 issue covering the situation in Japan:

The number of the people saved by Sigihara’s visas exceeded 6,000. Many of them managed to leave Japan for the USA but over a thousand remained in the country due to the rigid US immigration quotas.

Before covering further the activities of Japan in helping Jews, let me emphasize that most of what I covered is unknown to the average person, even in Japan. There is a significant volume of academic research in this field, but most of it has not found proper coverage in the media. The reason is that we are still dealing with the paradigm that the government of a country allied with Nazi Germany could do no good. Japan and Bulgaria are treated this way.

In the case of Japan, Sugihara is usually the only positively recognized person. His activities are often presented as a “conspiracy of goodness”, in which a lone hero defies the hostility of the “fascist” Japanese government. Shortly before his death, he was granted by Israel the title “Righteous among the Nations”, which is bestowed upon people who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The problem is that Sugihara did not risk his life. At the time, the National Socialist policies focused only on deportation of Jews, so a diplomat giving away visas was welcome to do so.

Besides, Sugihara was giving away visas, i.e. documents that would let a person enter a country. As the US rules today say, a visa does not guarantee entry, and things were no different in Japan in 1940. If the Japanese government had such strong objections against Sugihara’s defiance, they would have sent back all refugees, but they did not. They accepted even those with problematic visas. For comparison, imagine a good-hearted German diplomat who issues transit visas to Jews through Germany to, let us say, England. How long is he going to last and what will happen to the visa holders in Germany?

Another myth about Sugihara is his harsh treatment by the Japanese government. Two years ago, at a presentation I had at a Toronto synagogue about Japan and the Holocaust, an elderly lady rose up during the Q&A session and with an ominous accusatory voice let me know that because of his help for the Jews, Sugihara was fired by the Japanese government and “died a pauper”. This is how deep the misinformation goes. Although the Foreign Ministry was not happy with so many refuges entering the country, there were no repercussions for Sugihara. After Kaunas, he was transferred to the consulate in Prague, where he issues more visas, then to Konigsberg, East Prussia, and eventually ended up as a diplomat in Bucharest, Romania, where he was detained with his family at an Allied camp until 1947.

When he returned to Japan, the Foreign Ministry operated at a skeleton crew level. Japan had no diplomacy under the American occupation and there was no job for Sugihara. After struggling in different businesses, he finally landed a job in trading company in Moscow due to his fluency in Russian, where he worked for 17 years.

It is important to note that while at the Nuremberg trials the Holocaust became a major issue, at the Tokyo tribunals against the army and the government of Japan, the activities to help the Jews were never brought up. Sugihara was never called to testify. Anything that could give a better image to Japan was deliberately covered up.

Meanwhile, until mid-March 1941, Japanese consulates in Europe issued transit visas to 5,580 people. Sugihara’s Kaunas consulate issued more than 2,500 visas, and the rest came from other key locations in Europe. According to information of Japan’s Foreign Ministry provided in March 1941, Jews had entered Japan with transit visas from the consulates in Berlin, Moscow, Vienna, Hamburg, Stockholm, Prague, Sofia (Bulgaria), Riga (Latvia), and Kaunas.

By the summer of 1941, over 5,000 Jewish refugees residing in Japan had moved to other countries, but after the financial aid coming from the USA stopped due to various embargos, the Japanese government decided to transfer the remaining transit visa holders to Shanghai. The established Jewish communities in Kobe, Tokyo, and Yokohama were not affected. The process was accelerated after Japan entered the war with the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941.

Meanwhile in Shanghai, the Jewish refugees struggled to find work because the majority have skills that were not useful in an Asian city. In 1941, Laura Margolies from the US Joint Distribution Committee, arrived in Shanghai to re-organize the system for refugee support. Initially, she managed to get money to feed the destitute, but after Japan entered the war, the US Treasury banned all financial transactions since Shanghai was considered a hostile territory. Margolies had to rely on the help of Captain Inuzuka to transfer money through neutral countries.

Further pressure came from the police attaché at the German Embassy in Tokyo Col. Josef Meisinger, one of the creators of the Warsaw ghetto. In 1943, he tried to convince the Japanese administration in Shanghai to exterminate all Jews, but the Japanese refused to comply. Still, they caved under a demand to limit the movements of the “stateless refugees”, mostly Jews whose countries no longer existed. The older Sephardic community and the Russian Ashkenazi Jews were not affected. The stateless were confined to the so-called Shanghai Ghetto, an area within the Japanese sector. It was nothing like any European Nazi ghetto – the refugees were renting houses and apartments and living among Japanese and Chinese. Many found jobs in the area, but the majority worked in other parts of Shanghai and had to get passes to leave the “ghetto”. In mid-1945, the area was bombed by the Americans, about 40 refugees perished, along with many more Japanese and hundreds of Chinese.

While Japan found itself in a situation where it helped the Jews, the situation of the Allies who were supposed to fight Hitler’s anti-Semitism was more peculiar. I already mentioned the Evian Conference where over 30 countries refused to accept Jews and Palestine, the proposed future home of the Jews, was excluded from consideration, while a strange destination like Kenya was considered. Shortly after the Kristallnacht, President Roosevelt refused to increase the immigration quotas for Jews.

In November 1938, the Legislative Assembly of the US Virgin Islands proposed an increase in the number of refugees, but Roosevelt was not interested. Similar proposal came from Alaska and even though it called for only 10% of Jews among the new settlers, it was still rejected. In the early 1939, another proposal called for allowing 20,000 German refugee children into the USA over two years, but even the Jewish organizations did not support it, afraid of possible backlash. In May 1940, a plan to open Alaska to refugees was rejected.

The worst blow came on May 17, 1939, when the British Government issued the MacDonald White Paper, which declared that establishing of a Jewish state was not a policy of Great Britain since it was against the Arab interests. This was a blatant violation of the Mandate for Palestine. The Paper promised to create Palestine as an independent state within 10 years, with Jews as a minority. Further Jewish immigration was allowed only with Arab consent, but no more than 75,000, at the maximum of 10,000 per year for the next 5 years. After the beginning of World War II, the British government arrested over 1,000 Jewish men from Germany and Austria residing in the country, labeled “enemy aliens”. They were deported to Canada in June 1940 and kept there in labor camps with German POWs. Eventually, the number grew to 2,284 Jewish men and boys, all held in Canadian camps, where they were forced to work under harsh conditions.[2]

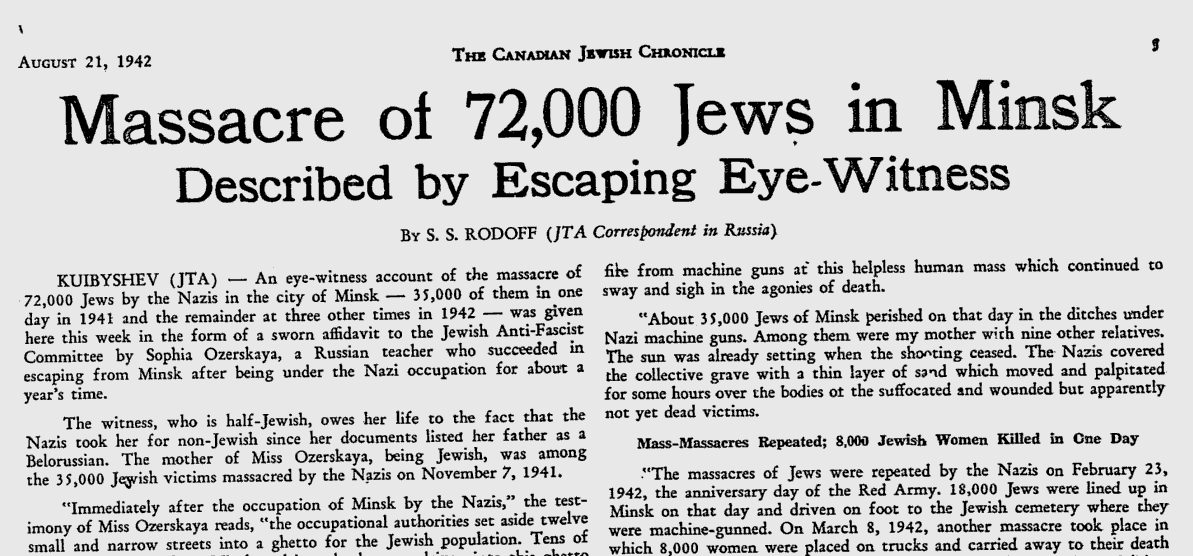

In mid-1942, when the magnitude of the Holocaust became known, President Roosevelt met at the White House Stephen Wise, leader of the American Jewish Congress, and five other leaders of major Jewish organizations. They presented him with a booklet detailing the slaughter of Europe’s Jews. Roosevelt expressed shock and sympathy but made no promise of U.S. action on behalf of the Jews. The promise he kept making until his death was that a quick war victory would resolve the Jewish problem. The War Refugees Board, supposed to protect the Jewish refugees, was created in early 1944 when 90% of the victims of the Holocaust were already dead.

The opposite attitudes in treating the Jews may make you think that Japan could receive some credit, especially when compared to the West. However, this has not happened. The reasons are deep and mostly based on racial hostility. The initial expansion of Japan into Korea, Manchuria, Formosa, and parts of China mirrored similar actions of Great Britain, the USA, and the Netherlands in the same area. Any of those countries was involved in various excesses or atrocities, like Great Britain in India, especially with the horrible famine in Bengal in 1943, which cost the lives of 3 million people. The USA was also involved in excesses in its war in the Philippines in the end of the 19th century3[3]. However, these events are rarely mentioned, while any atrocities of Japan, real or exaggerated, are constantly scrutinized.

In his article, Mr. Szagun finds the Japanese wartime behavior strange. He writes that the US soldiers, while taking Pacific islands from the Japanese one by one, through the so-called “island leaping”, were puzzled that their enemy would fight to the last cartridge, willing to shoot themselves with the last bullet instead of surrendering. Civilians did the same and even mothers with children preferred to jump from a cliff than to be captured. Further, Mr. Szagun notes that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were welcome because they put the Japanese in a position of victims, although their effects, if radiation is ignored, were similar to the conventional bombardments and the devastation came from using exclusively wood in the house construction.

These are interesting points, and they can be understood from the history of the interactions between the Japanese and the West, which makes it clear that bigotry and racism have always been present.

It is a well-known fact that for centuries Japan was a closed society. The pressure to open it came from the USA with the black ships of Commodore Matthew Perry. The Americans saw Japan as a tool to expand its trade with China and other Asian countries. “In Perry’s instructions the Japanese are described as a “weak and semibarbarous people,” the “most common enemy of mankind,” who needed to be compelled, either militarily or diplomatically, to respect the citizens and vessels of “civilized states” by entering into treaties to open their ports.”[4] It was an inequal relationship from the start.

When the Japanese started immigrating into the USA and Canada after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, it did not take long for hostility to build up against them. Worried by the spectre of the “yellow peril”, the host countries introduced various restrictions to prevent the Japanese from becoming too influential. Things became worse after Japan began to assert itself in the area, emulating the colonial powers that had already a firm presence in Asia. It was viewed as an intruder, even though the Western countries were also intruders in East Asia.

After the long chain of events of the 1930s culminated into the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941, all of the accumulated racism exploded into a constant stream of bashing. The USA fought both against Germany and Japan. However, the attitude toward both nations was radically different. While Germans were considered “evil”, they were still “like us”, bearers of similar customs and culture. On the other hand, Japanese were openly dehumanized, likened to “rats” and “monkeys” and treated accordingly within North America and on the battlefield.

A good example are the two covers of Time Magazine, both from 1941, depicting Adolf Hitler and the Japanese Admiral Yamamoto, the mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack. Hitler appeared several times on the cover of Time, but was depicted respectfully, even after it was clear what kind of a villain he was. Here, if you ignore the swastika armband, he looks like a respectable but decisive stateman. On the other hand, Admiral Yamamoto appears like a grotesque creature, straight from the laboratory of Dr. Frankenstein.

James Weitgartner points out that in Germany, the images of the enemy were imposed by totalitarian agencies on the basis of pseudo-scientific racist ideology, while in the USA the animosity was based on antipathy toward colored races in general, which after Pearl Harbor turned its focus exclusively on the Japanese[5].

The hostility was expressed at many levels. “The governor of Arkansas, referring to the soon-to-be interned Japanese residents of the West Coast, declared, “The Japs live like rats, breed like rats and act like rats.” Near the war’s culmination, President Harry Truman observed “The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast.”[6] “General John DeWitt of the U.S. Western Defense Command opined that the Japanese threat could only be eliminated by destroying the Japanese as a race. Paul McNutt, chairman of the War Manpower Commission, stated that he favored the complete extermination of the Japanese people. In May 1943, Captain H. L. Pence of the U.S. Navy, a member of a State Department committee shaping policy for postwar Japan, recommended “the almost total elimination of the Japanese as a race.””[7]

On the battlefield, such racist attitudes materialized in extreme hatred, which, as we will see, in most cases led to battles of extermination with a few or no prisoners taken.

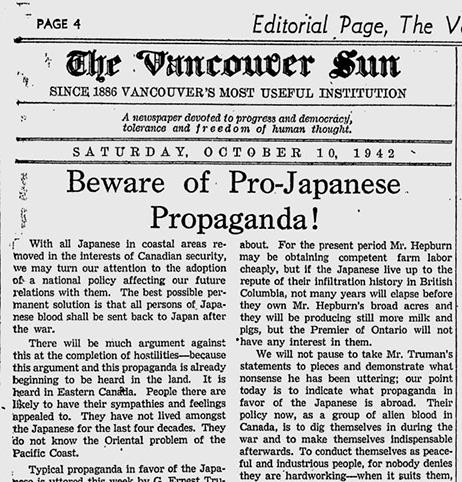

The dehumanization of the Japanese made easier the mistreatment of civilians in the USA and Canada. In the USA, it took a simple Executive Order of President Roosevelt to send over 120,000 Japanese, most US citizens, to internment camps without any proof of wrongdoing or proper legal process. The fate of the 24,000 Canadian Japanese was similar – they were sent from the coast of British Columbia to the eastern provinces without any due process. Their property was confiscated. The Canadian press touted the potential threat of Japanese sabotage on the West Coast or other areas, but the threats never materialized.

Even after the deportations, the press kept the anti-Japanese campaign alive like in this editorial published in the Vancouver Sun on October 10, 1942:

“Beware of Pro-Japanese Propaganda!

With all Japanese in coastal areas removed in the interests of Canadian security, we may turn our attention to the adoption of a national policy affecting our future relations with them. The best possible permanent solution is that all persons of Japanese blood shall be sent back to Japan after the war.

There will be much argument against this at the completion of hostilities because this argument and this propaganda is already beginning to be heard in the land. It is heard in Eastern Canada. People there are likely to have their sympathies and feelings appealed to. They have not lived amongst the Japanese for the last four decades. They do not know the Oriental problem of the Pacific Coast.”

A note in Maclean’s, Canada’s national newsmagazine, echoed the jubilation and did not miss the chance to attack the “Japs” again:

“B. C. Coast clear of Japs, British Columbia

THE JAPS are gone and British Columbia hopes to have seen the last of them. The B. C. Security Commission promised to have all the Japanese moved from coastal areas by the end of September, and it is clear that West Coast citizens are determined that Japanese residents of Canada will never again be concentrated in those vulnerable coastal regions. The Vancouver Sun has launched a campaign to assure the expatriation of all Canadian Japanese after the war and urges that this be included in the terms of peace. Vancouverites have also been reading with interest reports of conditions found after the Japanese exodus from their city’s “Little Tokyo.” Though the Japanese are commonly considered to be a cleanly race, indescribable filth and squalor were discovered. Some premises have been condemned by civic authorities as unfit for human habitation, and the city intends to reclaim the whole district for the use of Canadian citizens.”[8]

Canadian politicians kept fighting to get rid of the Japanese for good:

Even the advertisers jumped on the “anti-Jap” bandwagon, like in this ad for Buckley’s cough syrup:

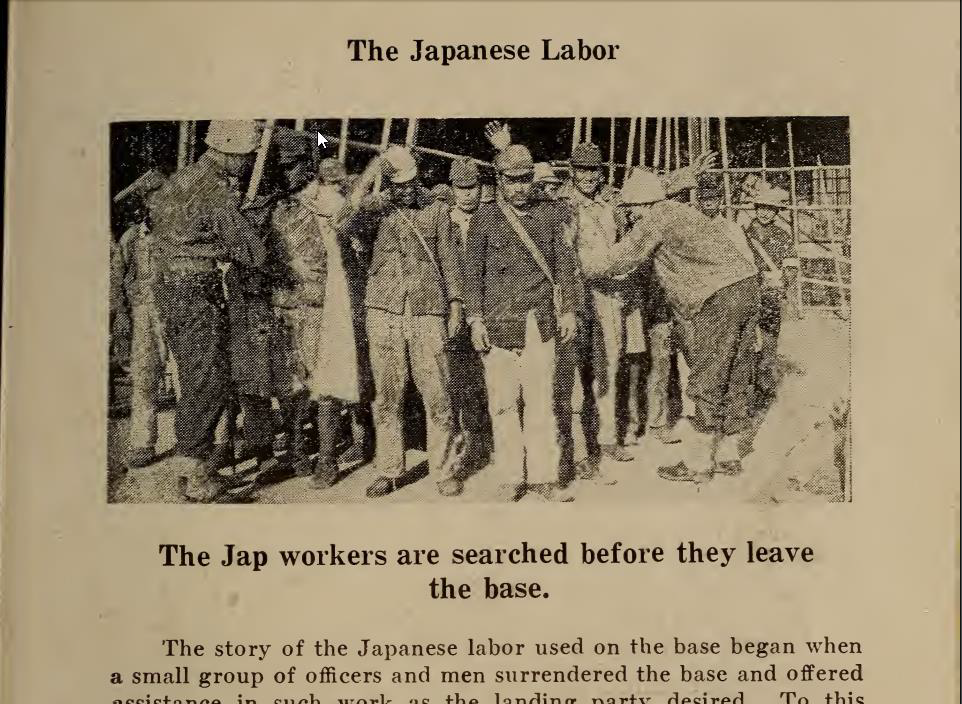

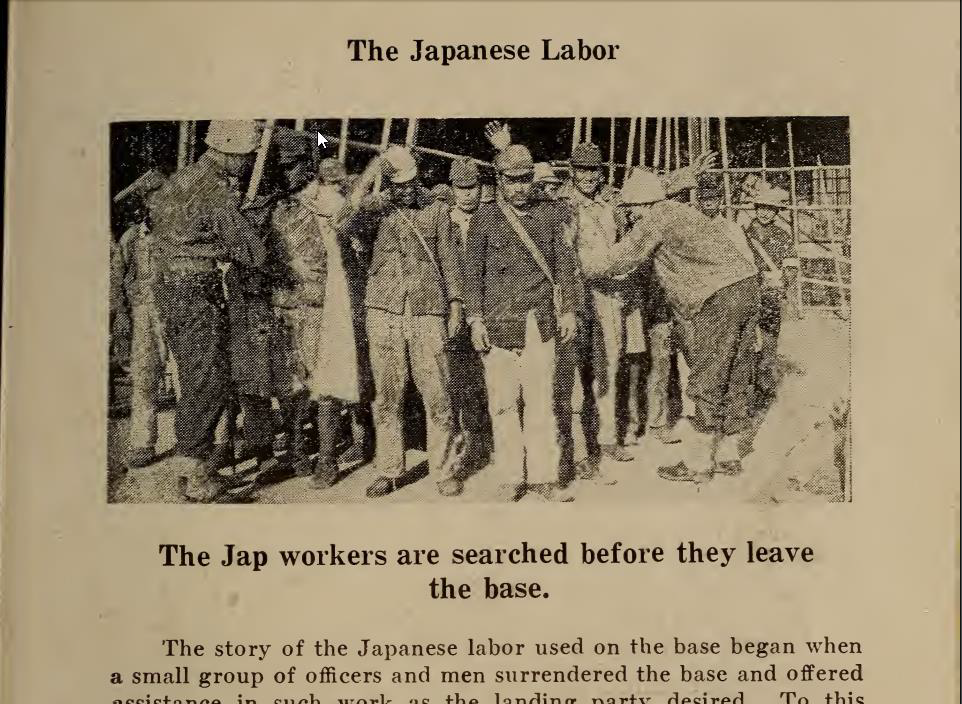

The casual racism continued even in Japan, after the defeated country was occupied by the USA. In a booklet published by Marine Aircraft Group 31 in Japan, we can find the following “uplifting” remark in the chapter “The Japanese Labor”: “All workmen have been given nicknames — it’s an American custom. The man’s appearance, the way he works will lead to a nickname. There are men called Tony, Jake, Slim, Big Stoop, and boys called Junior, Sleepy, Weasel, Smiley, and Monkey. They are proud of their nicknames.”[9]

Even General Douglas MacArthur adhered to similar racist views when he was in charge of Japan’s occupation after the war. He thought that the Japanese as a race were at the level of 12-year olds and stated it during Senate hearings in 1951: “Well, the German problem is a completely and entirely different one from the Japanese problem. The German people were a mature race. If the Anglo-Saxon was say 45 years of age in his development, in the sciences, the arts, divinity, culture, the Germans were quite as mature. The Japanese, however, in spite of their antiquity measured by time, were in a very tuitionary condition. Measured by the standards of modern civilization, they would be like a boy of 12 as compared with our development of 45 years.”[10]

On the battlefield or rather the open ocean where most of the battles took place, the brutality was unmatched. In his book “Silent Victory – the U.S. Submarine War against Japan”, Clay Blair, Jr., describes the activities of the famous American submarine Wahoo and its commander Mush Morton.

In the spring of 1943, the submarine attacked a Japanese transport, hitting one of the ships. After the explosion, the thousands of soldiers aboard her “commenced jumping over the side like ants off a hot plate.” Then the submarine dived to pursue another target. “When Wahoo surfaced, Morton ordered all deck guns manned. He found himself in a “sea of Japanese.” The survivors of the transport were hanging on the flotsam and jetsam or huddling in about twenty boats, ranging from scows to little rowboats. Grider wrote: The water was so thick with enemy soldiers that it was literally impossible to cruise through them without pushing them aside like driftwood. These were troops we knew had been hound for New Guinea, to fight and kill our own men, and Mush, whose overwhelming biological hatred of the enemy we were only now beginning to sense, looked about him with exultation at the carnage.

“Yeoman Sterling, who was topside, remembered the scene this way: The water was filled with heads sticking up from floating kapok life jackets. They were scattered roughly within a circle a hundred yards wide. Scattered among them were several lifeboats, a motor launch with an awning, a number of rafts loaded with sitting and standing Japanese fighting men, and groups of men floating in the water where they had drifted together. Others were hanging onto planks or other items of floating wreckage. A few isolated individuals were paddling back and forth toward the center in search of some human solidarity.

“Sterling remembered, roughly, an exchange between Roger Paine and Mush Morton: “There must be close to ten thousand of them in the water,” said Roger Paine’s voice. “I figure about nine thousand five hundred of the sons-a-bitches,” Morton calculated. Whatever the number, Morton was determined to kill every single one. He ordered the deck guns to open fire. Some of the Japanese, Morton said later, returned the fire with pistol shots. To Morton, this signaled “fair game.” What followed, Grider wrote, were “nightmarish minutes.” Later, Morton reported tersely, “After about an hour of this, we destroyed all the boats and most of the troops.” Leaving the carnage, Morton now took up the pursuit of the remaining two ships…”[11]

While the Japanese are constantly accused of lack of a war moral code, this incident proves that the Americans did not possess it either. In article covering a sea battle near New Guinea a few months later, Time Magazine did not seem have problem with exterminating people: “A new wave of Fortresses came over, low. Flame cloaked a destroyer. A 5,000-ton merchantman burst open. Four others were hit. Low-flying fighters turned lifeboats towed by motor barges, and packed with Jap survivors, into bloody sieves. Loosed on the Japs was the same ferocity which they had often displayed. This time few, if any, Japs in battle green reached shore.”[12]

The attacks were not limited only to military sea transports. The Americans targeted even Japanese hospital ships, which is a war crime, pure and simple. In volume five of the collection “Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1944, The Near East, South Asia, and Africa, The Far East” (available online) you can find letters and memorandums exchanged between the USA and Japan regarding bombings of several Japanese hospital ships in 1944[13].

The dehumanization of the Japanese enemy led many Americans to see it as prey. “If the Japanese were animals, some Americans saw themselves as stalking prey. In some parts of the United States, official-looking ‘hunting licenses’ were distributed to young men to encourage them to enlist. ‘Open Season. No Limit. Japanese Hunting License. Free Ammunition and Equipment! With Pay. Join the United States Marines!’ Just like big-game hunters, some of them came home with trophies to prove their prowess.”[14]

Eugene Sledge, a Marine who wrote well-known war memoirs, shared his experiences with collecting “souvenirs”: “I noticed gold teeth glistening brightly between the lips of several of the dead Japanese lying around us. Harvesting gold teeth was one facet of stripping enemy dead that I hadn’t practiced so far. But stopping beside a corpse with a particularly tempting number of shining crowns, I took out my kabar and bent over to make the extractions.” At that moment, the unit’s doctor approaches him and tells him to stop. The doctor is concerned with the germs that may spread from the corpse. “I stopped and looked inquiringly at Doc and said, “Germs? Gosh, I never thought of that.” “Yeah, you got to be careful about germs around all these dead Nips, you know,” he said vehemently. “Well, then, I guess I’d better just cut off the insignia on his collar and leave his nasty teeth alone. You think that’s safe, Doc?” “I guess so,” he replied with an approving nod.”[15]

On another occasion, Sledge discovers that a comrade of his is carrying with him a decomposing severed hand of a Japanese soldier. The American still thinks he can dry the hand: “Aw, Sledgehammer, nobody’ll say anything. I’ve got to dry it in the sun a little more, so it won’t stink,” he said as he carefully laid it out on the rock in the hot sun. He explained that he thought a dried Japanese hand would be a more interesting souvenir than gold teeth. So, when he found a corpse that was drying in the sun and not rotting, he simply took out his kabar and severed the hand from the corpse, and here it was, and what did I think?”[16]

In another war chronicle, “Guadalcanal Diary”, its author Richard Tregaskis writes about his talk with a few Marines before disembarking on an island on July 31, 1942: “A lot of it was about the Japs. “Is it true that the Japs put a gray paint on their faces, put some red stuff beside their mouths, and lie down and play dead until you pass ’em?” one fellow asked me. I said I didn’t know. “Well, if they do,” he said, “I’ll stick ’em first.” Another marine offered: “They say the Japs have a lot of gold teeth. I’m going to make myself a necklace.” “I’m going to bring back some Jap ears,” said another. “Pickled.” The marines aboard are dirty, and their quarters are mere dungeons. But their esprit de corps is tremendous.”[17]

The “souvenir” hunting involved collecting the possessions of the dead and often their body parts. “Sometimes the Americans did not bother to wait until their victims were dead before they methodically emptied their pockets and packs, took their guns and knives, flags, helmets, photographs, identity tags, knocked out their teeth, and sometimes cut off their ears, their fingers and, occasionally, their heads”[18]. Some of the military personnel went even further by boiling the severed Japanese heads to de-flesh them. “In October 1943, the US Army’s high command was alarmed at newspaper reports concerning a soldier ‘who had recently returned from the southwest Pacific theater with photos showing various steps “in the cooking and scraping of the heads of Japanese to prepare them for souvenirs”’. Today, it is easy to find photographs online of Allied soldiers boiling human heads in old fuel drums to remove the flesh, and pictures of severed Japanese heads hanging from the trees.”[19]

It was well-known that such treatment of the war dead contradicted the 1929 Geneva Convention, and the War Department discouraged the practice but not much was done to expose the violators.

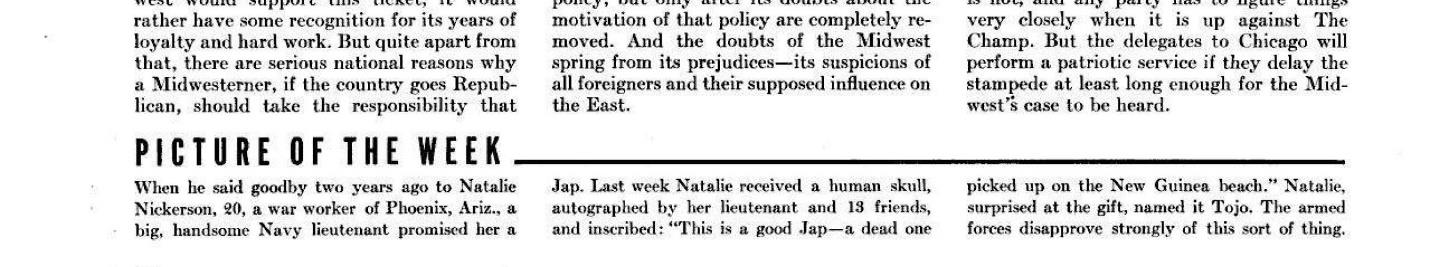

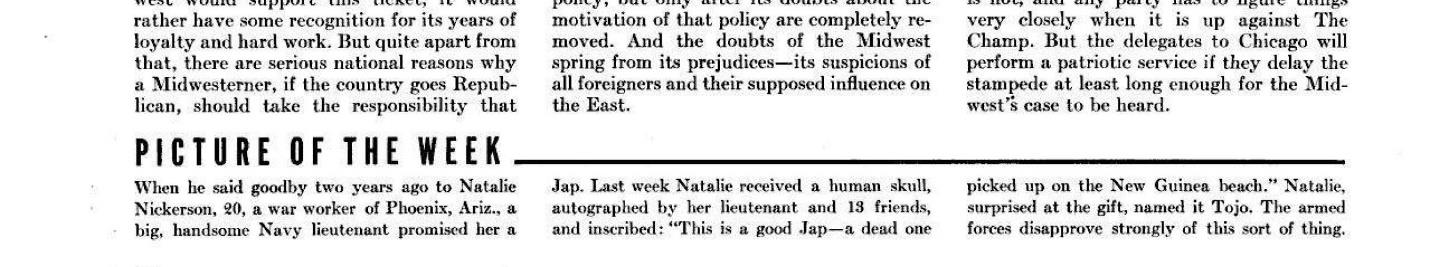

The body parts collection activities eventually caused an international scandal. In one of its issues, Life Magazine published as its ‘Picture of the Week’ the photo of a young lady writing a letter and contemplating a skull sitting on her desk. The caption read: “When he said goodby [sic] to Natalie Nickerson, 20 a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends and inscribed: “This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach.” Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo.”[20] The magazine added that the armed forces discouraged such sort of things.

The photo reached Japan and caused a storm of indignation. Another incident, a month later, caused similar outrage. “On June 13, 1944, there had appeared in the New York Mirror a column by the noted commentator Drew Pearson describing the presentation to President Franklin D. Roosevelt by Pennsylvania’s Congressman Francis Walter of a letter-opener purportedly fashioned from an arm bone of a Japanese soldier. The congressman was reported to have been apologetic for presenting the President with “so small a part of the Japanese anatomy.”[21] The incidents forced the military authorities to curb on such practices, though they continued in different forms until the end of the war. As of Roosevelt’s gift, after the scandal broke, he returned the bone letter opener to the congressman in August 1944.

Japanese civilians were treated with similar disrespect and became military targets despite the assurance that Americans do not bomb civilians. Earlier, I quoted Mr. Andreas Szagun’s statement that Japan’s cities were targets of “conventional bombing”. This is not entirely correct – the bombs developed in 1943-1944 were not conventional. They were “incendiary”, designed to cause much wider damage by burning and suffocating people. They were used with devastating effects in Dresden, Hamburg, Sofia, Tokyo, Osaka, and other Japanese cities. Initially, there was a conflict between Air Force General LeMay and General MacArthur. The latter opposed the new bombs because they would destroy the cities of the people that the Americans were liberating. The position of LeMay for “necessary” bombing with no regard for the consequences prevailed. “MacArthur did not have to deal directly with the issue of bombing Japanese civilians during his operations, but in June 1945 one of his key staff aides called the fire raids on Japan “one of the most ruthless and barbaric killings of non-combatants in all history.””[22]

The US servicemen were horrified with the consequences of the incendiary bombing of Tokyo on March 9, 1945. “Before Operation ‘Meetinghouse’ was over, between 90,000 and 100,000 people had been killed. Most died horribly as intense heat from the firestorm consumed the oxygen, boiled water in canals, and sent liquid glass rolling down the streets. Thousands suffocated in shelters or parks; panicked crowds crushed victims who had fallen in the streets as they surged toward waterways to escape the flames.

Perhaps the most terrible incident came when one B-29 dropped seven tons of incendiaries on and around the crowded Kokotoi Bridge. Hundreds of people were turned into fiery torches and “splashed into the river below in sizzling hisses.” One writer described the falling bodies as resembling “tent caterpillars that had been burned out of a tree.” Tail gunners were sickened by the sight of hundreds of people burning to death in flaming napalm on the surface of the Sumida River. A doctor who observed the carnage there later said, “You couldn’t even tell if the objects floating by were arms and legs or pieces of burnt wood.” B-29 crews fought superheated updrafts that destroyed at least ten aircraft and wore oxygen masks to avoid vomiting from the stench of burning flesh. By the time the attack had ended, almost sixteen square miles of Tokyo were burned out, and over one million people were homeless.”[23]

In a conversation with the military correspondent Nikolai Bogdanov, an employee of the Soviet embassy in Tokyo shared similar memories about the bombing of the city: “The American dropped their incendiary bombs in a special way to create rings of fires. No matter where the Japanese tried to run, they were met by a wall of fire. The authorities sent tanks to help the running crowds. They tried to open escape paths through the burning houses, but the tanks caught fire as well. People jumped into water to escape the fire, there are many canals and even home pools here. But the heat was so strong that the water in the small pools was boiling and people suffocated in the larger pools. Later, they took out thousands of corpses from pools and canals. They say that no less than 200,000 Japanese died from fire and suffocation.”[24]

In 1945, the Allies were seriously considering the use of poisonous gas against the Japanese.[25]

In 1945, at the liberation of Buchenwald, the Americans arranged an exhibit of a table with shrunken heads and other body parts, which appeared in the first documentary shot in the camp. Later, Nazi guards and police were tried at the Nuremberg and other trials for these atrocities. Collecting gold teeth from inmates was another grisly crime for which Nazis were known, especially when those teeth were deposited in banks, as it was revealed at the Nuremberg trial. Yet similar crimes against Japanese were ignored then and still are ignored today.

The problems of the Japanese continued even after the war. At the time of the capitulation, over 6 million Japanese were outside of Japan. The American occupation authorities managed to repatriate most of them. However, about 600,000 remained in the Soviet Union, used as slave labor after being captured during the Russian invasion of Manchuria. Nearly 1 million Japanese civilians there abandoned, thousands of women were raped or killed.[26] (This was a war crime under the rules of the Nuremberg trial, but Great Britain and the USA had no problem with it.) Eventually, the Russians returned the infirm and feeble POWs, the healthiest and brightest Japanese POWs were selected for indoctrination in camps and Soviet Marxist schools. A newspaper for them, Nihon Shimbun, was printed to popularize Soviet propaganda among Japanese.[27] In June 1949, a large group of about 2,000 robust and healthy but brainwashed POWs returned to Japan. They yelled “We are entering enemy territory!” and sang the International. They declared they would join the Communist Party and fight the Americanization of Japan. They were followed by many similar groups.[28]

Large groups of Japanese soldiers who surrendered to Chinese forces were forced to work or be used in battles on either of both sides of the civil war in China. “More than a year after surrender, it was reported that some sixty-eight thousand Japanese taken prisoner in Manchuria were still being employed by Chinese forces, mostly on the communist side. The Kuomintang (Nationalist) government, for its part, delayed the repatriation of over fifty thousand Japanese with useful technical skills for much of 1946. As late as April 1949, on the eve of the communist victory, more than sixty thousand Japanese were still believed held in communist-controlled areas… In Manchuria alone, it is estimated that I79,000 Japanese civilians and 66,000 military personnel perished in the confusion and the harsh winter that followed capitulation. Uprooted civilians in Manchuria and elsewhere in northern China usually were able to bring with them only what they could carry, which commonly meant little more than their smallest children and paltry, soon-to-be-exhausted quantities of food.”[29]

As we see, Japan has had many problems and its people are not to be blamed for all of them. However, Mr. Szagun is not happy that the Japanese were not humiliated enough. When mentioning the official atomic bomb museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he laments that they “merely depict the side of the civilian victims, and the East Asian victims of the brutal military expansion are not mentioned.” Incinerating civilians with atomic bombs or incendiary bombs is a war crime, regardless of the fact that the perpetrators were never charged. Telling the story of the victims is what is important, making the museum an exhibit on how they deserved what was coming to them is disrespectful.

Mr. Szagun uses similar approach when condemning the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, the Shinto temple dedicated to the war dead of Japan, which he says is offensive to Japan’s neighbors. He finds the military museum near the shrine even more offensive: “Japanese war technology is exhibited, and the war is literally glorified, for example with atmospheric dioramas. Kamikaze missions, i.e. suicide by means of flying bombs, are also portrayed as patriotic by displaying a corresponding aircraft and explaining it.“ (“Japanische Kriegstechnik wird ausgestellt und der Krieg, zum Beispiel mit stimmungsvollen Dioramen, regelrecht verherrlicht. Auch Kamikaze-Einsätze, also Selbstmord mittels fliegender Bomben, werden durch das Zurschaustellen eines entsprechenden Flugzeugs und den Erklärungen dazu als patriotisch dargestellt.”)

I have visited that museum – it covers the whole military history of Japan with exhibits and artifacts. The Pacific War is part of that history. Sure, it is unnerving to see “midget submarines” (kamikaze torpedoes) and other similar devices, but they are also part of history. The “glorification” comes from the letters and statements of the pilots displayed in that section. From observing the exhibition, an intelligent person can make his own conclusions, and this is the essence of learning from history. Hiding or destroying the bad will ensure that the bad will eventually repeat itself. At a time when the Japanese were considered “monkeys” and “rats” in civilized America, their soldiers were exterminated even after surrendering, and hundreds of thousands of women and children were incinerated by Allied bombs, maybe the kamikaze was a desperate reaction.

Besides, such frightening relics from World War II are preserved in the West. ‘Enola Gay’, the infamous airplane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, is preserved at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia. They also hold at least one kamikaze flying bomb, Kugisho MXY7 Ohka (Cherry Blossom) 22. Will Mr. Szagun condemn that museum as well?

While the Yasukuni Shrine museum presents real things that Japan’s neighbors may resent because they do not reflect their tastes, most of those neighbors have museums and shrines that grossly distort history. I have visited all of them, except for North Korea.

Let me start with Chairman Mao Zedong’s mausoleum, which hosts the embalmed corpse of Mao in a dimly lit hall at Tiananmen Square. This is one of the three mausoleums I have visited, the other being Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow and the now-defunct mausoleum of Georgi Dimitrov (Bulgaria’s first communist dictator). Mao’s mausoleum is regularly visited by the highest ranks of the Chinese Communist Party, led by Chairman Xi.

Mr. Szagun who is willing to lecture Japan over its past, may not be aware that Mao was one of the worst mass murderers in human history, beating Hitler and Stalin combined. Yet, instead of being confined to the dustbin of history, Mao is still the beacon that points the path of China. Is the little museum at Yasukuni Shrine more dangerous than Mao’s shrine?

While I was visiting Beijing, I also went to the Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution. Mr. Szagun will probably find some similarities between it and the Japanese museum. The big problem is that compared to the Yasukuni museum, the monstrous Beijing building is a fantasy land, which has very little to do with history. The World War II period is strongly distorted showing non-existent victories of Mao’s army at the time when they were hiding from the Japanese in Yanan and sporadically fighting Chiang Kai-shek. None of the atrocities committed by that army was shown – there was no Tibet invasion, Uyghur crackdowns, the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and the Tiananmen Square massacre. Maybe Mr. Szagun finds communist atrocities acceptable?

Another fake museum in China was the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum. As its name shows, it commemorates the Jewish refugees who fled Europe to escape the German National Socialists. I outlined in detail above what happened at the time and how Japan was the driving force behind the rescue. There is nothing of that in the Shanghai museum – everything done on behalf of the Jews was done by China. Maybe people like Mr. Szagun are happy to accept lies if they come from communist China instead of peaceful Japan?

Another Chinese tourist attraction is the Mausoleum of Genghis Khan in Inner Mongolia, China. Adjusted for percentages of the world population at the time, the Khan beats Hitler, Stalin, Mao and a few other lesser dictators combined in the number of people he killed. Is he better of worse for Japan’s neighbors than the Yasukuni Shrine?

One more dictatorial resting place I have seen was the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei, Republic of China (Taiwan). There is an impressive statue of the Generalissimo inside, but there is no note, as Mr. Szagun requires for museums, indicating that he was responsible for one of the worst ecological disasters in history. In June 1938, to stop the advancement of the Japanese Army, Chiang Kai-shek ordered the destruction of the Yellow River dykes in the Zhengzhou area. The action harmed his own people – over 890,000 were killed and 3,900,000 fled the area and it did not stop the advancement of the Japanese.

The War Memorial of Korea, a.k.a. the Korea Army Museum in Seoul, South Korea was another large museum with an impressive collection. It also included a large exhibition section about the participation of the South Korean army in the Vietnam War with reconstruction of events, replicas of people in uniforms, etc. The only thing missing was the real record of that invasion. The 300,000 soldiers strong Korean army committed mass atrocities in Vietnam where thousands of people died. They raped about 30,000 Vietnamese women and the thousands of children born to them led miserable existence because South Korea never admitted guilt and never paid any compensations.

Only an ignorant person can direct hatred toward Japan over events from the distant past and ignore realities that are plaguing its neighbors.

With all that said, the next statement of Mr. Szagun sounds strange and hypocritical: “On another issue, however, Japan still struggles very hard with its neighbors and former opponents of war: unlike in Europe, there has never been state-level reconciliation. For example, if Germany and France were almost “eternal hereditary foes”, today almost no one would come up with the idea of attacking the other country. Both the official German-French cooperation and friendship, as well as youth encounters, are sought in vain in the East Asian region. Japan has almost never admitted its war guilt or sought reconciliation gestures toward its neighbors.”

It is difficult to give Europe as an example. France and Germany may have improved their relations, but the problems in the old continent persist, especially between Eastern and Western Europe on the issues of immigration. As of the Far East, the only country that has changed was Japan. China and the two Koreas are entangled in problems much more important than the war past.

Japan was subjected to a forceful transformation since the first days of the Allied occupation. It lost control over its education institutions and foreign policy. Under severe censorship, over 7,000 book titles were destroyed or banned. Textbooks at all levels of education were rewritten to reflect the imposed “war guilt program”. Japan paid reparations. It is ridiculous to claim that it never admitted war guilt. The problem is that some forces are pressing it to admit “additional” guilt over things that did not happen.

At the same time, China went through a bloody civil war that killed millions of people and brought to power the Chinese Communist Party. Its leadership led the country through horrific social experiments like the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. Both caused the death of tens of millions through murder and starvation. In 1950, it invaded Tibet causing a genocide with about a million dead Tibetans. The cultural genocide of imposing the Han language and norms practically wiped out the rich and unique Manchurian culture, today, out of 10 million Manchus, less than 20 speak their language. Similar fate faced the people from Inner Mongolia.

The reforms in the 1979 only strengthened the power of the communist party. Now it can use high-tech surveillance to oppress its citizens. It is constantly expanding its military arsenal; artificial islands are built to place military installations. The Uyghur minority is subjected to violence and about a million are sent to indoctrination camps. “Month after month, inmates say, they are drilled to renounce extremism and put their faith in “Xi Jin-ping Thought” rather than the Koran. One told us that guards ask prisoners if there is a God, and beat those who say there is. And the camps are only part of a vast system of social control.”[30]

Today, China has added new targets of its atrocities. The vicious persecution of the Falun Gong Buddhist sect being one of them. The practitioners are arrested, tortured and killed and their organs harvested for transplants. Nothing like this is even conceivable in Japan. The new “social credit” system in China makes the dissidents real outcasts – their negative record stops them from even the most normal activities, like travel, because they are not even allowed to buy railway tickets. It is another unthinkable option in Japan.

Taiwan lives under the constant threat of invasion. The recent crackdown on the dissidents in Hong Kong put an end to its autonomy. China’s influence goes far beyond its borders – it disputes islands that belong to Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines. The idea that this totalitarian bully is hurt by the reluctance of Japan to cave to its demands over old history is ludicrous.

China has no restrains when trying to impose its agenda on other countries. Last month, the Ambassador of China to Canada threatened the Canadian government: “ “We strongly urge the Canadian side not (to) grant so-called political asylum to those violent criminals in Hong Kong,” Ambassador Cong Peiwu said in a video press conference from the Chinese Embassy in Ottawa. …”So if the Canadian side really cares about the stability and the prosperity in Hong Kong, and really cares about the good health and safety of those 300,000 Canadian passport holders in Hong Kong, and the large number of Canadian companies operating in Hong Kong SAR, you should support those efforts to fight violent crimes,” Cong said.”[31]

There is no better testimony about the communist evil that rules the People’s Republic of China.

North Korea is an even worse case. It is the world’s largest concentration camp, where people have no real rights. It is even more threatening than China because it has nuclear weapons. It has been abducting Japanese citizens for decades, their number is estimated to be over 800. Japan has received little help in its international efforts to bring them back. North Korea operates a real fifth column in Japan comprising of hundreds of thousands of Koreans with allegiance to the communist Kim dynasty.

Very little attention is paid to them outside of Japan, yet they are often behind many blackmail campaigns against the country, even though they benefit greatly from the society they despise. They are united in a powerful organization called Chongryun. This organization “takes as its mission the unity of Koreans in Japan around the government and leadership of North Korea, and there are Koreans who call themselves overseas nationals of North Korea.”[32]

The organization closely mirrors the communist structures that existed in Eastern Europe and are still alive and well in North Korea. “Founded in 1955, Chongryun consists of a complex of numerous associations affiliated to the main organization. The central headquarters, situated in Tokyo, has authority over all the local chapters, covering the forty-eight prefectures of Japan. There are eighteen affiliated organizations, including the Youth League, the Women’s Union, the Young Pioneers, Teachers’ Union, Merchants and Industrialists Union, Artists’ Association, Scientists’ Congress, and so on. Chongryun has a professional football club and theater companies. Twenty-eight independent commercial companies are associated with Chongryun; among them is the Kumgang Insurance Company. Chongryun’s bank, Choshin, divides Japan into thirty-eight blocs with a total of 188 branches… The way in which these organizations are arranged is evidently similar to the North Korean (and Soviet) style, where the central party has satellite organizations for women, youth, and children as well as occupational organizations such as farmers’ leagues and workers’ congresses. Chongryun has one university, twelve high schools, fifty-six middle schools, eighty-one primary schools, and three independent nursery schools. There are also nursery schools attached to the primary schools. The first language of Chongryun Koreans born in Japan is Japanese, but lessons in Chongryun schools are taught in Korean; Japanese is taught also… The schools teach about North Korea, and children learn that they are overseas nationals of North Korea. All the textbooks used in Chongryun schools are published by its own publisher, the Hagu Siibang Publishing Company.”[33]

Their schools are fine examples of communist brainwashing. “We Are the Happiest Children in the World, Thanks to Our Father Marshal Kim Il Sung!” These words are normally inscribed on a large panel on the roof terrace of a Chongryun school. As you approach the classroom, you can hear children repeating after the teacher in loud voices in Korean: “Happy New Year, Father Marshal! The new year dawns. The round sun rises. All of us gather together and send our greeting to Father Marshal: Happy New Year, Father Marshal Kim Il Sung! We wish you a long, long life.” The walls of the classroom are decorated with slogans and posters. Portraits of Kim II Sung and Kim Jong II are placed high on the front wall, while the framed “teachings” of the two Kims are neatly hung on each side of the blackboard. Slogans read, “Let Us Be Faithful Children of Our Father Marshal!” (Ibid., p.23). The schools have been funded by North Korea since 1957. “Journals and other books for students are published by Chason Chongnyonsa, another of Chongryun’s publishers. The editing process is supervised by Chongryun’s Education Department; no Japanese authorities are involved. In contrast, all Japanese school textbooks are censored by the Ministry of Education.”[34]

The same type of education is received at the Chongryon-run university – Korea University, established in 1956. “At the end of every day, every week, every month, each term, and each academic year, there is a review session consisting of self-criticism and group criticism. A set of check questions, a kind of review manual, focuses on certain points, for example,

- Have you fulfilled the assignments given by the organization (i.e., Youth League)?

- Have you completed the study assignments required by the course?

- Have you been honest to your comrades?

- Can you say that your conduct has been in accordance with the patriotic ideal of the organization?

- Can you say that you have displayed enough loyalty to the Great Leader and the Dear Leader?”[35]

Since the time Sonia Ryang’s book was published, the influence of the organization had somewhat diminished, because it was implicated in financial improprieties, but it is still an important factor in undermining Japan.

On the surface, South Korea looks like the most democratized of the three most vocal neighbors of Japan, but it has a streak of totalitarianism, which is due to its traditions and not just to the strong communist influence. For many decades, the country kept under lid one of its worst atrocities – the Bodo League massacre in 1950, during the Korean War. In the summer of that year, it is estimated that between 110,000 and 200,000 civilians were executed for alleged sympathy to communism.

Since South Korea has been the face of the campaign to vilify Japan over the World War II, it is important to note that, aside of the Bodo League massacre, it has even more skeletons in its collective closet.

As I mentioned above in the paragraph about my visit to the Seoul military museum, the section about the Vietnam War did not tell the whole truth. The military dictator, a.k.a. President Park Chung Hee, sent over 300,000 South Korean soldiers to fight in Vietnam on the side of the Americans. In exchange, he received more military aid. The Korean troops massacred from 8 to 10 thousand innocent civilians and raped thousands of Vietnamese women. No government official, even the disgraced daughter of Mr. Park, President Park Geun-hye, recognized the events.

A 71-page report on the US Army covering the atrocities committed by the Korean troops in Vietnam can be accessed online.[36]

As The Guardian writes: “Roughly 320,000 South Korean soldiers were deployed to Vietnam to fight alongside the US between 1964 and 1973, but the story of the country’s involvement in the conflict is largely untold. South Korea has never acknowledged claims of sexual violence allegedly perpetrated by its troops against thousands of women and girls, some as young as 12 – or the children born as a result.

“However, South Korea has continued to demand apologies from Japan for its use of “comfort women” from Korea, who were forced to work in Japanese military brothels before and during the second world war. …“Lai Dai Han” is a pejorative term meaning “mixed blood” in Vietnamese. The Vietnamese-Korean children say their lives have been blighted by stigma in a society that has acknowledged neither them nor the sexual violence suffered by their mothers. Many are illiterate because they were refused an education, and they have poor access to healthcare and social services.”[37]

It is not clear how many Lai Dai Han live in Vietnam. According to different estimates their numbers vary from 5,000 to 30,000. However, this is a dangerous field to research, because it may offend a special interest group in Korea, which can file a defamation lawsuit. And according to the Korean law, a statement can be considered damaging even if true. This is what happened to the researcher Ku Su-jeong: “… An October 30, 2016, article in The Hankyoreh said that Jang Ui-seong, head of the Vietnam Veterans’ Association of Korea (VVAK), was representing 831 plaintiffs in a defamation lawsuit against Ku Su-jeong for Ku’s 2014 interview in the Japanese newspaper Shūkan Bunshun, Ku’s 2016 interview in the The Hankyoreh and Ku’s statements in a video. The article said that South Korean “veterans’ organizations” of the Vietnam War have said that Ku’s claims of the alleged actions of the South Korean military during the Vietnam War have “all” been a bunch of “falsehoods and forgeries”.”[38]

Veterans’ organizations blocked an event that was supposed to be held at Jogyesa Temple in Seoul on Apr. 7, 2015, which victims of the civilian massacres during the Vietnam War were planning to attend. Veterans have dismissed all the victims – regardless of age and gender – as having been “Viet Cong disguised as civilians.” For the veterans, the Viet Cong were enemies who needed to be killed. They claim that no sexual violence occurred and that it was the Viet Cong who lopped off the breasts of female victims.[39]

An article written by Noriyuki Yamaguchi, chief of the Washington bureau of the Tokyo Broadcasting System (TBS) dealt with his research in the US military archives on the activities of the Korean troops in Vietnam: “According to the article, the letter makes reference to the illegal diversion of large amounts of US supplies by the South Korea military in Vietnam. One of the places mentioned as a backdrop for the crime was a “Turkish bath for South Korean troops” located in central Saigon. The letter also reportedly refers to “acts of prostitution taking place” and “Vietnamese women working” at the Turkish bath. “While it is a welfare center exclusively for South Korean troops, US troops are also able to make special use for a fee of US$38 per visit,” the letter is quoted as saying.”[40]

Of course, the hypocrisy of the situation, where Koreans are accusing somebody of crimes they themselves did is lost to them. Organizations in Canada and other places come up with outrageous accusations, like the claim that the “comfort women” were distributed as gifts by the Emperor of Japan, which is shown in a cartoon displayed at a Korean “Peace Fest” in Toronto in August 2015 (“gift” is inscribed on the girls’ clothes):

Questioning of the official version of the “comfort women” issue in South Korea is also a dangerous endeavor. Getting harassment and various death threats is part of it, as the historian Park Yu-ha found out. “On October 27 [2017], the Seoul High Court overturned the acquittal of Park Yu-ha, a Sejong University professor and expert in Japanese-Korean relations, fining her US$8,846 for defaming victims of Japanese wartime sexual slavery, known as “comfort women”, with her 2013 book Comfort Women of the Empire. …After Park’s indictment for defamation in November 2015, 54 scholars – including MIT professor Noam Chomsky and University of Chicago professor and Korean history expert Bruce Cumings – issued statements in her defence. But the factual accuracy of the book was irrelevant because in South Korea, a statement does not have to be false to constitute defamation – it merely has to be considered damaging. …Under the Lee and Park administrations, defamation charges were often used to silence journalists or academics. In fact, about 160 journalists were punished under Lee for writing material deemed critical of the government. Park continued that legacy, targeting entertainment personalities and sport figures as well.”[41]

The disgraceful judicial system of South Korea seems to be a good copy of the Stalinist “justice”, very useful when historical lies need to be defended.

This is a frightening picture. Japan has not been involved in a single act of military intimidation since the end of the war, while its neighbors present a real military danger.

Mr. Szagun is either unaware or willfully ignorant of the situation when he blasts Japan for plans to change Article 9 of its Constitution, which prohibits the use of an army. He claims that the conservatives and the ultra-right are behind the attempts to abolish Article 9. He states: “Although the majority of the vote is conservative, many Japanese are very uncomfortable with the idea of what an abolished Article 9 could mean for Japan’s future.” The Constitution was adopted during the Occupation when Japan was a protectorate of the USA and the latter took full responsibility for Japan’s defense. China and Korea were in total disarray at the time, not a real threat. Fast forward to today – both China and North Korea are dangerous military powers, while the USA is in disarray and can barely cope with its internal problems. The only forces that benefit from keeping Japan helpless and defenseless are China and the two Koreas. It is not hard to figure out whose interests represent the communist Koreans and the Japanese “peace activists” in Japan.

To give you an impression on how the “comfort women” issue is discussed and promoted in public, I would like to draw your attention to a panel discussion. It took place on May 3, 2016, at OISE (Ontario Institute for Studies in Education), faculty of the University of Toronto, Canada. Although the topic was: “The Apology: Colonial and Militarized Sexual Violence Against Women”, most of the vitriolic statements were reserved for Japan. Special guest was the “comfort woman” survivor Gil Won Ok and Yoon Meehyang, feminist activist and a director of the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, was the keynote speaker. I have posted a video covering most of the event here:

https://vimeo.com/165920935/9821db3376

Ms. Yoon repeated the claim that 200,000 women were abducted by the Japanese government and forced into sex slavery. She did not provide factual evidence and relied mostly on anecdotal “evidence” from about 500 survivors and most of them are losing their memories or want to forget the events. On top of that, she did not explain why South Korea raised the issue decades later. She claimed that Prime Minister

Ms. Yoon repeated the claim that 200,000 women were abducted by the Japanese government and forced into sex slavery. She did not provide factual evidence and relied mostly on anecdotal “evidence” from about 500 survivors and most of them are losing their memories or want to forget the events. On top of that, she did not explain why South Korea raised the issue decades later. She claimed that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was refusing to face the “truth” because his grandfather was supposedly a war criminal. The apology of December 2015 was not enough – they wanted the Japanese to accept full guilt and provide more money. They also expected Japan to change the history textbooks to reflect the guilt.

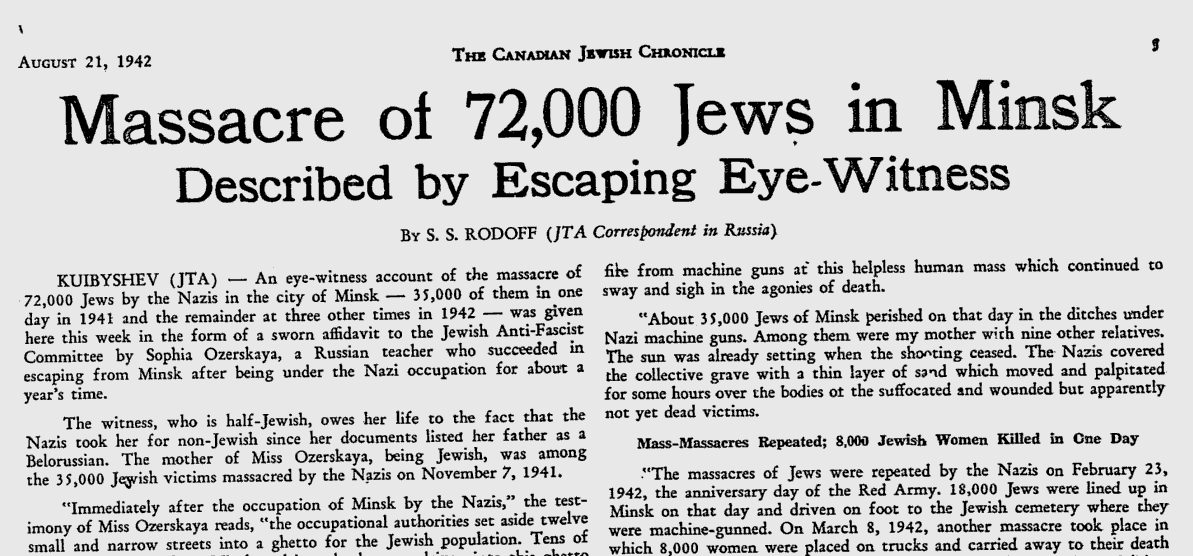

Let me note here that a few years ago, South Korea presented “documents” regarding this issue to be included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Program, comparing the “comfort women” case to the Holocaust. A ridiculous comparison – the documenting of the genocide against Jews started in the early 1942 when the news reached Europe and America. Since then, the collection of facts, documents and names has never ceased. If you have visited the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem, you would have seen that the main goal of the remembrance is to give names to the faceless victims and find out everything about them. That is why, despite all the revisionist attempts, the Holocaust is impossible to refute – all facts have been painstakingly collected for decades. The “comfort women” issue does not meet that standard, it came to public attention only in 1990s, which would be important to maintain if its defenders throw such serious accusations against Japan.

I was curious about her fact sources and asked about them during the Q&A session. She said that a crucial evidence was a report commissioned by General MacArthur in 1945: “Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces”. I am familiar with this document; it describes, among other things, brothels used by the Japanese army but does not make any claims or allusions about forced sex slavery. (Other sources present a similar picture – see, for example, this collection: Lt. Col. Archie Miyamoto, U.S. Army (ret.). Wartime Military Records on Comfort Women: A Compilation od U.S./Allied/Dutch/Japanese Military Documents, Amazon, 2017, ISBN 9781980350057). As I will point out below, the US occupation army maintained similar brothels in Japan for its soldiers and officers.

Ms. Yoon said that after the earthquake in Japan in 2011 many women from the disaster area have been raped and her organization provided material support to the victims – $50,000 – and also sent them packages with underwear with a message from the surviving “comfort women” in each package. This was another accusation in the paradigm of “Japanese barbarism”, so I asked about the sources. She vaguely referred to some “women’s organizations in Japan” as her source.

I could not find any evidence of such rapes. On the contrary, people around the world were impressed with the orderly response and the lack of any looting. The government and thousands of volunteers responded immediately. Even Yakuza, the Japanese Mafia, started to deliver within hours food and water to the survivors. A few months later, I visited the area for a research, trying to get as close as possible to the Fukushima nuclear power plant. On the way we passed through many villages that were evacuated due to possible radiation. The empty streets were guarded by small police patrols. Some of them, after a few apologies, checked the trunk of our car but admitted that not many come to the area and they had not caught any thieves. They were called for duty to the affected area from various parts of Japan to serve for a month. Unfortunately, close to Fukushima, we were turned back by army units who said that it was too dangerous to continue. Of course, such facts mean nothing to those who blackmail Japan to advance their agenda.

Mr. Mayor, in his open letter to you published after his article was released, Mr. Szagun asks you how seriously your statements against the female genital mutilation could be taken if, due to interference of a foreign power, the naming of a terrible crime against women is prevented. Then he raises again the example of the reconciliation between Germany and France that shows how things can be done differently. Finally, he urges you: “Why don’t you get involved in Japan’s internal affairs and show how things could be better if you wanted to?”

In other words, you will have no moral authority to judge crimes against women, unless you single out Japan and lecture it on its past. I think I already showed that the vocal neighbors of Japan conceal monstrous crimes for which they have not taken responsibility. Shouldn’t you be required to get involved in their internal affairs as well in order to restore justice?

But why go all the way to the Far East? You can address an injustice in your own country. It is a well known fact that in the end of World War II, millions of German women were raped by soldiers from the Allied troops, mostly Russian, but also American and Canadian, during the occupation of Germany proper and the violent ethnic cleansing of East Prussia, Poland, Sudetenland, and other areas populated by ethnic Germans.

I remember, during a visit to the German Democratic Republic years ago, how any discussion of the war events, especially violence against civilians, was taboo. The country was practically still occupied by the Russians and the prevailing official attitude was that the civilians got what they deserved in retaliation for the policies of Hitler’s National Socialist government.