島根県議会が平成25年(2013年)6月26日 に可決した『日本軍「慰安婦」問題への誠実な対応を求める意見書』は、河野談話、米国下院決議121、国連人権委員会勧告を受け入れて日本政府に対応を求めるものでした。

この意見書の撤回にむけて、島根県の有志が署名、抗議文、集会など様々な取組を行ってきました。

※「島根県有志の取り組み なでしこアクションブログより」参照

令和5年2月定例会にも意見書撤回を求める19回目の請願を提出しましたが、今回も不採択となりました。不採択を続ける議会に対して意見表明する成相議員の発言はこちらです。是非ご覧になり、島根県議会の現状と請願者の訴えをお聞きください。

<島根県議会 令和5年2月定例会 3月3日 本会議 録画>

59分59秒~ 成相 安信 議員 討論

https://shimane-pref.stream.jfit.co.jp/?tpl=play_vod&inquiry_id=1117

<請願第50号を不採択とした委員長報告に反対する討論>

請願第50号、安倍総理の「将来の世代には十字架を背負わせたくない」という政治家としての崇高な理念が、性奴隷も強制連行も認めたものではないという「河野談話本質」を反映した2015年の日韓慰安婦合意を導きました。

しかし、世界中に建てられた慰安婦像の碑には「日本軍は少女や女性を強制連行し性奴隷にした」と書かれています。その根拠とされるものは「河野談話」しかありません。

平成25年6月26日付で決議された“日本軍「慰安婦」問題への誠実な対応求める請願”並びにこれを基にして政府に出された意見書は海外に建つ慰安婦像の碑文同様に、河野談話の解釈を誤っています。

したがいまして無効とする決議を求めます。(文中では平成25年を2013年と記載します)

を不採択とした委員長報告に反対する討論を行います。

今期に入って毎議会ごとに出された同趣旨の請願は15回を数え、請願者は県議会の理解が得られるよう意を尽くし、誠実に請願文書を様々な角度から作成し提出を重ねてこられました。

しかしこの4年間、そのような努力にもかかわらず、島根県議会はまともな議論をおこなわず、請願者の訴えに向き合わないまま今日を迎えました。否、議論を行わないというより反論する論拠をだれも持つことができず、結果、これを無視し続け苦し紛れに数の力で握りつぶしてきたというべきでありましょう。

まったく残念という他ありません。請願文書で主張される中身が正確に問題整理され、妥当性を強めていくほどに、そしてそれがさらに15回も総括的に反対討論で重ねられてきた主張を耳にすれば、何もわからなかった議員でさえいやが上でも理解が進んだはずであります。

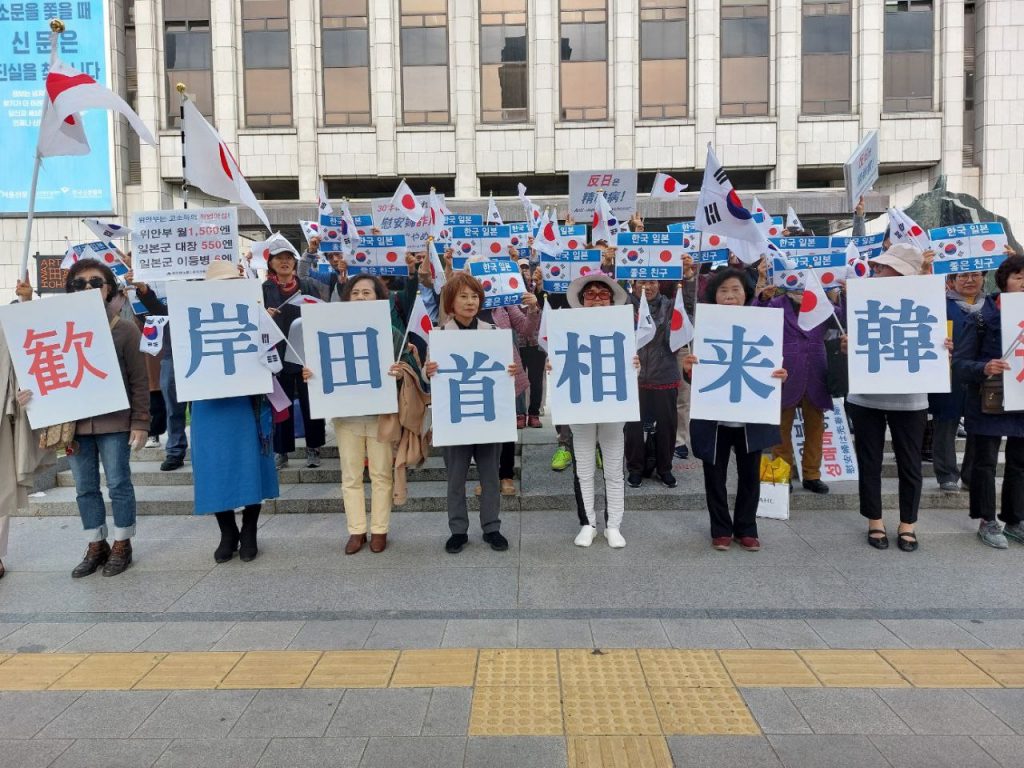

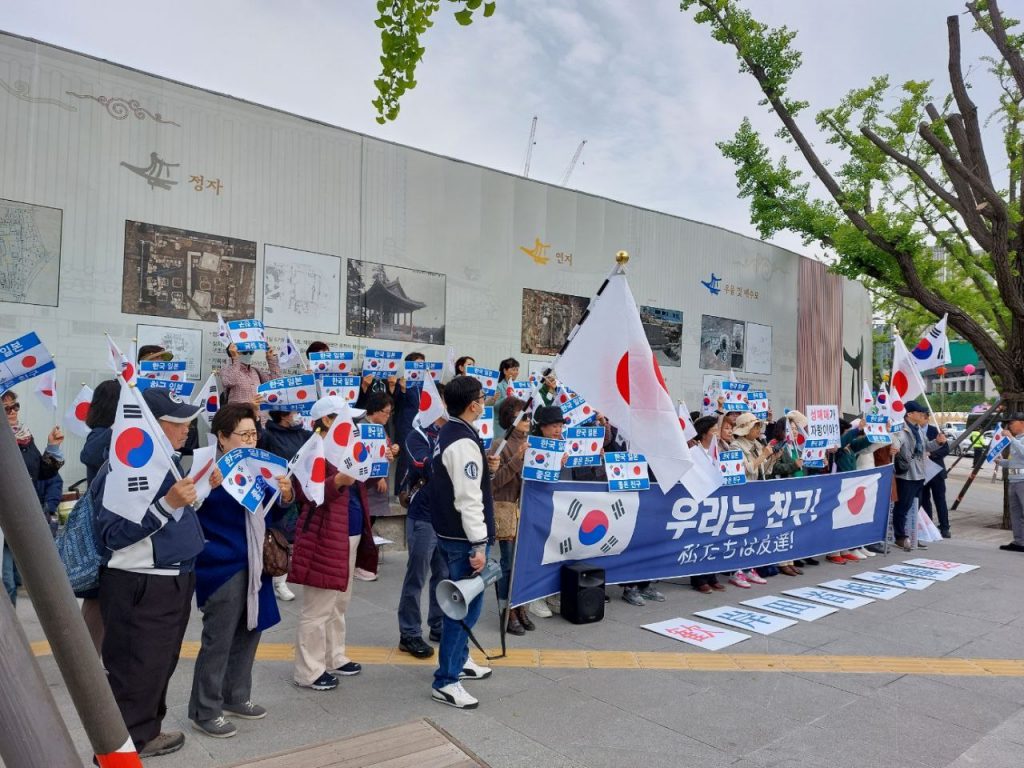

韓国では悪夢のような文在寅政権が終焉し、ユン・ソンニョル大統領の誕生で徴用工問題や慰安婦問題など歴史認識問題が政治利用される度合いが薄まりつつあるように見えます。日韓関係を未来志向で臨みたいとする姿勢の表れだとも論評されています。それは我が国の慰安婦を巡る政府検証や有識者による数々の実証的研究論文によって国民理解が進み、加えて安倍首相の毅然とした外交姿勢が日韓両国内の誤った歴史認識是正に影響を与えていることは明らかであります。

近年、韓国国内でも有識者たちが国内の政治勢力の圧力をものともせず、反日的歴史認識に対する誤りを正すべく立ち上がっています。島根県議会を始め「良心的日本人」の間ではなお吉田清治氏や朝日新聞の主張を支持する日本人が多いですが、請願文書でもこれまで主張されてきた様に、「慰安婦問題」自体がこうした一部の日本人から出発していると指摘され、こうした動きこそが韓国と日本を仲たがいさせ良心的では決してないのだと批判されています。

慰安婦問題のうそが広く韓国社会で理解されるにつれ反日的感情を利用してきた「良心的日本人」は、韓国でも日本でも孤立し立つ瀬がなくなるのだとの韓国からも改めて強調されています。

島根県議会は、2005年小泉総理や一部自民党の反対を押し切って「竹島の日」条例を制定したことは画期的な事でした。当時議席を有する議員たちの勇気ある見識をもった決断でした。しかしそれに水を差し、台無しにしてしまっているのが現下の「慰安婦決議」です。

「竹島の日」制定を契機に、韓国は今日の「東北アジア歴史財団」を発足させ、歴史戦で日本をやり込める報復戦に乗り出しました。島根県の竹島資料館では県内大学生がボランティアで説明にあたっていますが「竹島問題」の説明にとどまっています。「竹島の日」から派生したといえる慰安婦問題や徴用工問題など歴史認識問題は一体のものであり、それぞれについての説明も併せて行わなければ韓国の世論や動きが理解出ないと思いますが、県は県議会のこれまでの動きを忖度してか進めようとしません。県議会はもとより、県行政当局も歴史認識問題について大きく後退している事も問題であります。

今日様々な視点から安全保障論議が高まっていますが、領土問題や歴史認識問題への対応の遅れが、安全保障を脅かし経済的損失を招いているばかりではなく、将来にわたって対外的な日本の信頼や名誉にかかわる大きな問題なのだと認識を新たにすべきだと考えます。

請願第50号採択をお願いし、以下請願者から寄せられた意見をここにご紹介したいと思います。

先月、22日の竹島の日の山陰中央新報一面に、竹島問題研究会の座長下條正男教授の論文が掲載されていました。その中で下條教授は次のように記しておられます。

「歴史的に竹島が韓国領であった事実がないのと同様に、徴用工問題も徴用工ではなく、慰安婦問題もこれと似ている。当初日本兵を相手にしていたのでは自尊心が許さないとし、何とか強制されたことにしてほしい、として始まったのが慰安婦問題である。その事実を確認しないまま公表した「河野談話」によって、慰安婦問題は日本の国家的犯罪にされ、反省と謝罪が求められたのである。」

この翌日の中央新報にも前日の記念式典での下條教授の講演の概略が記されています。そこには「竹島問題も徴用工や慰安婦問題も同様だと言い。理詰めで矛盾点を指摘すべきだと説いた。」 とあります。

下條教授が、多くの論文や講演で慰安婦問題を持ち出され、その認識が県議会の意見書とは全く異なるものであることを、議論していくことは、今や竹島問題解決のためには避けられないものとなっています。

韓国では「慰安婦とは戦時の公娼制だった」との実証研究が行われるようになり、昨年、11月に提出した請願書には韓国の金柄憲(キムビョンホン)氏の著書に書かれている次の文章を引用しました。

「日本軍慰安婦問題の本質は「貧困」だ。国が貧しく親が貧しいから食べていく道を探しているうちに、悪の沼に陥ったケースがほとんどである。これ以上他人のせいにするのはもうやめたい。」

金柄憲氏が言われる「悪の沼」に陥っていたのは、それを容認していた旧日本軍も同様でした。

旧日本軍が慰安婦に関与したのは今日の価値観では容認できないものですが、当時の時代背景を考慮すれば致し方ない面もあり、真実を基に検証していけば教訓とするべきものも少なくありません。

日本政府が河野談話の翌年の1994年に「女性のためのアジア平和国民基金」を設立したのも、2015年の日韓慰安婦合意に際に10億円を拠出したのも、今日的な価値観によるお詫びと見舞いのものです。

ここで県議会での委員会などの討論を振り返ってみますと、時間の経過とともに「強制連行説」を唱える主張が明らかに弱くなっていることが分かります。

例えば令和元年6月定例会の本会議では「日本軍慰安婦問題は、日本が起こした侵略戦争のさなかに植民地にしていた台湾、朝鮮、中国などで、女性たちを強制的に集め、性行為を強要した非人道的行為である。」という、現在では考えられないような、内容が本会議で堂々と語られていました。

この発言はアメリカのグレンデール市の慰安婦像の碑を始めとして、世界中に広まるつつある碑に記されている、「日本帝国の軍隊によって東アジアの諸国において住居から狩りだされ、性奴隷にされた20万人以上のアジアとオランダの女性を記念して」といった無茶苦茶な話とほぼ同様の内容でした。

そして昨年の2月議会までは「強制連行であろうが、自分で手を挙げようが、そんなことは無い方が良い。河野談話の中で否定できないと、あった可能性があると言っている」という意見が度々見受けられました。これは強制連行があった可能性を残して、売春と組織的なレイプを同列において、間違った解釈をあえて誘引し、しかも組織的なレイプが否定されたとしても、この論理性であれば、発言の責任を問われないという意志が垣間見えるものです。

そして、昨年5月議会からは「島根県議会の意見書は女性の人権、人間の尊厳に関わる問題として河野談話に基づく我が国の誠意ある対応を求めて決議したもの」という、当該意見書の本質的な文言をから目をそらし、当該意見書から美辞麗句のみを抽出した、実態を反映していない無責任ともいえる発言に留まるようになりました。

島根県議会において平成25年6月26日付で決議された“日本軍「慰安婦」問題への誠実な対応を求める請願”並びに、これを基にして政府に出された意見書は強制連行説を認めるものであり、実際に当該意見書の基になる請願書には「強制連行を認めた」との文言が入っています。

冒頭に述べましたように、下條教授は講演や論文において毎回のように「慰安婦強制連行説」は虚構であると述べておられます。

島根県議会と下條教授の慰安婦問題の捉え方が、真逆であることは竹島問題の解決において、決定的な障害となるものです。

これらを無効とする決議は絶対に必要なことです。

よく考えてみて下さい。今生きている私たちも数年か、数十年の命です。

私たちのためにではなく、安倍元総理の「将来の世代には十字架を背負わせたくない」という思いを受け止め、未来に生きる子供たちが理不尽な困難に会わないためにも、そして今日の平和の礎を築いて下さったあまたの戦没者の方々の名誉のためも、速やかに無効とする決議を求めます。

以上、請願者からの意見を紹介し反対討論を終わります。

*******************************************************************

【 成相議員・有志が撤回を求めている意見書 】

島根県議会 平成25年6月26日 可決

日本軍「慰安婦」問題は、女性の人権、人間の尊厳にかかる問題であり、その解決が急がれています。

この問題について、日本政府は 1993 年「河野談話」によって「慰安婦」への旧日本軍の関与を認めて、歴史研究、歴史教育によってこの事実を次世代に引き継ぐと表明しました。

その後、2007 年 7 月には、アメリカ議会下院が「旧日本軍が女性を強制的に性奴隷にした」として、「謝罪」を求める決議を全会一致で採択したのをはじめ、オランダ、カナダ、フィリピン、韓国、EUなどにおいても同様の決議が採択されているところです。

また、日本政府は、本年 5 月 31 日、国連の人権条約に基づく拷問禁止委員会より、「公人による事実の否定、否定の繰り返しによって、再び被害者に心的外傷を与える意図に反論すること」を求める勧告を受けるなど、国連自由権規約委員会、女性差別撤廃委員会、ILO専門家委員会などの国連機関から、繰り返し「慰安婦」問題の解決を促す勧告を受けてきているところでもあります。

このような中、日本政府がこの問題に誠実に対応することが、国際社会に対する我が国の責任であり、誠意ある対応となるものと信じます。そこで政府におかれては以下のことを求めます。

記

1 日本政府は「河野談話」を踏まえ、その内容を誠実に実行すること。

2 被害女性とされる方々が二次被害を被ることがないよう努め、その名誉と尊厳を守るべく、真摯な対応を行うこと。

以上、地方自治法第99条の規定により、意見書を提出します。島根県議会

(提出先)

衆議院議長

参議院議長

内閣総理大臣

外務大臣

内閣官房長官

*******************************************************************

<参考 島根県有志の取り組み なでしこアクションブログより>

2023年2月9日付

竹島の日を前に「島根県議会の慰安婦意見書撤回を求める」有志のチラシ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17766

2023年1月15日付

「島根県議会の慰安婦決議の撤回を求めて」有志からの報告書

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17728

2023年1月6日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める18回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17717

2022年11月3日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める17回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17431

2022年6月24日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める16回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=17064

2022年3月24日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める15回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=16913

2022年1月4日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める14回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=16556

2021年10月26日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める13回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=16437

2021年8月8日

情けない島根県議会 いつまで性奴隷説にしがみつくのか?

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=16202

2021年7月14日

「慰安婦意見書撤回を求める請願」を拒否し続ける島根県議会

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=16107

2021年3月25日

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める11回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15778

2020年12月20日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める10回目請願不採択

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15513

2020年10月19日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める9回目請願不採択、10回目請願へ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=15192

2020年8月11日付

元高校野球監督 野々村直通氏、島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を訴える

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=14809

2020年8月4日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める8回目請願不採択、9回目請願へ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=14682

2020年3月24日付

島根県議会に「慰安婦意見書」撤回を求める7回目の請願

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=14391

2014年12月31日付

竹島を領有する島根県議会がこのままで良いのでしょうか?

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=7752

2014年9月29日付

日本を愛する島根女性の会「朝日新聞の大誤報を起因とする「河野談話」の即時撤回を要求する県民大会」

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=7140

2014年6月23日付

日本を愛する島根女性の会から県議会議長宛て抗議文

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=6582

2014年6月5日付

島根県議会「慰安婦」可決の説明を ネット署名3600人、提出へ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=6528

2014年4月13日付

竹島奪還を目指す島根県議会がなぜ「慰安婦意見書」?県議会議長に説明を求めます!

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=6265

2014年1月14日付

カルフォルニアの母の会が島根県議会に抗議!

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=5600

2013年12月12日付

島根県から報告「議長の椅子取りゲームに慰安婦問題を利用するのは許せない」

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=5440

2013年10月4日付

「島根県議会の歴史認識をただす 島根県民の会」から活動予定お知らせ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?p=5033

2013年9月9日付

島根県民が「慰安婦意見書」撤回に立ち上がった!

http://nadesiko-action.org/?page_id=4791

*******************************************************************

<参考 地方議会の慰安婦意見書について なでしこアクションブログより>

ねつ造慰安婦問題解決に向けて地方議会の意見書・決議・請願・陳情まとめ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?page_id=7180

地方議会の慰安婦意見書

http://nadesiko-action.org/?page_id=2

左派市民団体と国連のマッチポンプ

http://nadesiko-action.org/?page_id=7